Coordinators:

Gabriel Martín

Antonio Gutierrez

Rui Caratão

Mars Muusse

Home

lusitanius 1cy June

lusitanius 1cy Aug

lusitanius 1cy Sept

lusitanius 1cy Oct

lusitanius 1cy Nov

lusitanius 2cy Feb

lusitanius 2cy March

lusitanius 2cy April

lusitanius 2cy May

lusitanius 2cy June

lusitanius 2cy Sept

lusitanius 2cy Oct

lusitanius 2cy Nov

lusitanius 2cy Dec

lusitanius 3cy Feb

lusitanius 3cy Mar

lusitanius 3cy May

lusitanius 3cy June

lusitanius 3cy Sept

lusitanius 3cy Oct

lusitanius 3cy Nov

lusitanius 4cy Feb

lusitanius 4cy May

lusitanius 4cy Dec

lusitanius ad June

lusitanius ad Aug

lusitanius ad Sep

lusitanius ad Nov

lusitanius ad Dec |

adult: June

Below you find a copy of the article "Sex Differentiation of Yellow-legged Gull

(Larus michahellis lusitanius): the Use of Biometrics,

Bill Morphometrics and Wing Tip Coloration".

"we" in the text below refers to the original authors. The text has been added with most care, but if any errors occur, please let me know and mail to marsmuusseatgmaildotcom.

Sex Differentiation of Yellow-legged Gull

(Larus michahellis lusitanius): the Use of Biometrics,

Bill Morphometrics and Wing Tip Coloration

JUAN ARIZAGA, ASIER ALDALUR, ALFREDO HERRERO & DAVID GALICIA

IN: Waterbirds 31(2): 211-219, 2008.

A number of biological processes in

birds, such as diet and foraging (Holmes

1986; Durell et al. 1993; Clarke et al. 1998),

parental care (Pierotti 1981) or migration

(Swanson et al. 1999; Rubolini et al. 2004;

Cristol et al. 1999), differs between the sexes.

Accordingly, sex-identification is basic to understanding adequately all these processes

which, overall, give us key clues about the life

history of species. The Yellow-legged Gull

(Larus michahellis) is a circum-Mediterranean gull, breeding from Iberia to the Black

sea (Olsen and Larsson 2004). In Iberia two

subspecies currently breed (Bermejo and

Mouriño 2003; Olsen and Larsson 2004):

L. m. michahellis, occurring along Mediterranean coast, up to central Portugal in W Iberia, and L. m. lusitanius, in Atlantic coasts

from northwest Iberia, up to south central

Portugal (Pons et al. 2004). L. m. atlantis,

present in Macaronesia and the northwest

coasts of Africa, do not breed in Iberia (Bermejo and Mouriño 2003; Pons et al. 2004).

Among the large gulls (largest of Larus spp.), sexes differ in their size with males being larger (Ingolfsson 1969; Coulson et al.

1983; Bosch 1996), and there are a number of

studies dealing with discriminating methodologies used to distinguish between sex classes. Discriminating functions vary not only between species, but often also among populations (Evans et al. 1993). A number of studies

have focused on biometrics of a number of

Mediterranean Yellow-legged Gull populations (Carrera et al. 1987; Bosch 1996) in relation to sex, whereas studies on the Cantabrian Yellow-legged Gull are scarce and analyses on sex-differences are virtually lacking.

In addition to biometrics, the wing-tip

coloration patterns in several gull species

have been described to vary not only between species, but among age and sex classes

and populations (Coulson et al. 1982; Allaine

and Lebreton 1990; Saks and Rattise 2006).

Although in a number of large gulls these

patterns are thought to be independent of

sex (Mierauskas et al. 1991; Snell 1991), we

have no data on the Cantabrian Yellow-legged Gull populations. Bill size in gulls is

highly dimorphic between sex classes (Ingolfsson 1969; Coulson et al. 1983; Bosch

1996). However, it is virtually unknown if this

dimorphism is also observed in relation to

bill morphology (shape), as it is observed in

other seabird species (Kaliontzopoulou et al. 2006). Our aim was to obtain useful criteria

to distinguish sex in a population of Yellow-legged Gull L. m. lusitanius in the eastern Bay of Biscay, in relation to

(1) classical biometric variables,

(2) wing-tip patterns of coloration (black and white areas at the wing tip)

and

(3) bill morphology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling Area and Data Collection

Data on 155 dead adults (EURING code A, birds

with more than five years) of Yellow-legged Gull collected in a dump in Zarauz (43°17'N, 02°10'W, N Spain), in

the eastern Bay of Biscay, were used as a part of a government culling program. After labelling the specimens,

they were kept frozen (see for a similar method Bosch

1996) and, before taking measurements, they were

thawed. Only data on adults collected from early April

to early July were used to guarantee that measured gulls

were local. Thus, birds from other non-local populations, such as the Mediterranean Yellow-legged Gull

(L. m. michahellis), a relatively common winter visitant in

the Bay of Biscay (Yesou 1985; Martínez-Abraín et al. 2002) were avoided.

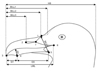

Within each gull, measures were taken of

(1) 25

feathers and skeletal-associated measurements (Table 1,

Fig. 1),

(2) 14 records associated with the size and features of white and black areas at the tip of the outermost

primaries (Table 2, Fig. 2; feather areas were taken with

a mesh to 1.0 mm2

accuracy, and lengths were recorded

with a digital calliper to ± 0.5 mm) and

(3) bill morphology, for which seven landmarks were established (Fig.

1). Within each landmark, two variables were recorded:

the x and y coordinates, so 14 records related to bill

morphology were obtained. In the first two sets of measurements, data on disarranged or growing feathers

were omitted. All measurements were recorded by a single author (AA). Most of the measurements had a low

proportion of fleshy tissue, so shrinkage should be minimal after freezing (Bosch 1996). |

Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga. Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga. |

Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga.

Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga. Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga.

Yellow-legged Gull lusitanius June 2007, Gipuzkoa, Basque. Picture: Juan Arizaga. Location: dump in Zarauz (43°17'N, 02°10'W, N Spain), in

the eastern Bay of Biscay.

Location: dump in Zarauz (43°17'N, 02°10'W, N Spain), in

the eastern Bay of Biscay. Figure 1. Head and bill-associated measurements (arrows)

and landmarks (dots 1 to 7) measured in each individual.

Figure 1. Head and bill-associated measurements (arrows)

and landmarks (dots 1 to 7) measured in each individual. lusitanius Yellow-legged Gull

lusitanius Yellow-legged Gull