Heuglin's Gull (L. heuglini / antelius)

Heuglin's Gull (L. heuglini / antelius)

(last update:

Amir Ben Dov (Israel)

Chris Gibbins (Scotland)

Hannu Koskinen (Finland)

Mars Muusse (the Netherlands)

adult heuglini: April

Is it possible to identify Baltic and Heuglin's Gulls?

By Chris Gibbins, IN: Birding Scotland 7(4), December 2004.

THIS IS PART 2

Context and aims of the paper

To summarise the above discussion, it may be argued that both fuscus and heuglini are

potential visitors to Scotland. Both have been discussed previously in this context (Gibbins

and Golley, 2000). A number of papers published in the 1990's improved our knowledge of the identification of fuscus and heuglini. In particular, they suggested that moult could

be used to support identification, including that of immature birds. These papers set new

standards. In the case of fuscus, they re-awakened interest and initiated a new and more

rigorous search for this taxon in Western Europe. In the case of heuglini, they brought the

details of its field appearance to our attention for the first time and raised the possibility of

its occurrence in the UK. Most recently, the gulls monograph (Malling Olsen and Larsson,

2003) was an opportunity to synthesise and consolidate knowledge of these taxa. Unfortunately, because of the mislabelling of so many plates in the first edition, this book

has not proved a reliable reference point. More particularly, critical errors remain in the heuglini section in the revised edition (discussed on page 172).

The remainder of this paper discusses current ideas on the identification of fuscus and heuglini. It is based on the author's observations of both taxa in Finland (2001, 2002 and 2004), the United Arab Emirates (2004) and Israel (2000 and 2001) and of graellsii and intermedius in Portugal (2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004) and the UK. The paper also draws upon field studies being undertaken by gull enthusiasts around Europe, the results of which have yet to be formally published. The focus is on the extent to which this recent work has affected our perceptions of fuscus and heuglini; in this sense, the paper is essentially an update to the work of Lars Jonsson and Visa Rauste.

Because of differences in the way ideas on their identification have evolved, each taxon is

treated in a slightly different way. For fuscus the discussion concentrates on the criteria

given by Jonsson (1998a) and the extent to which these are still seen as holding true. For heuglini the discussion is based largely around some individual birds ('case studies') and

whether they could be identified with certainty if encountered outside of the normal range

of this taxon. Overall, it is hoped that the paper improves awareness of these taxa among

Scottish birders who have no previous field experience of them, or not had access to the

literature. It concentrates on identification in the spring to autumn period as this is when

they are perhaps most likely to be encountered as vagrants in Scotland. No firm identification

criteria have so far been suggested for juvenile (first Calendar-year [1 cy]) heuglini,

while there are no known diagnostic features for 1 cy fuscus. The paper therefore concentrates

on birds in their second calendar year and older. As is now the convention for gulls,

primaries are numbered outwardly, with the inner primary being P1 and the outer primary

P10. As far as possible, ringed individuals (therefore of proven age and origin) are used to

illustrate identification features.

Identification of heuglini

Although treated by Grant (1986) as a subspecies of Herring Gull, heuglini is essentially a Lesser Black-backed Gull. As its separation from Herring Gull is therefore not a real problem, the following discussion concentrates on identification relative to the other Lesser Black-backed Gull taxa.

There are contrasting statements in the literature about the appearance (particularly the

size, structure and upperpart tone) of Heuglin's Gull. It seems most likely that, as with all

other large white-headed gulls, it is rather variable. However, some of the apparent

variability of Heuglin's Gull may actually reflect descriptions based on misidentified birds,

while some results from the inclusion of taimyrensis as the eastern form of Heuglin's.

There are relatively few photographs of heuglini in the English language literature. This and

the contrasting statements about its appearance have lead to some uncertainty among UK

birders as to what the field characteristics of heuglini are. The following text therefore

attempts first to build a general image of the appearance of heuglini and concentrates on

the issue of its apparent variability. This is followed by a discussion of the identification of

some individual birds – the 'case studies'.

(i) Size and structure

Grant (1986) described heuglini as large and long legged, "readily separated from fuscus by (its) much larger size and heavier build". The structure of taimyrensis was described by

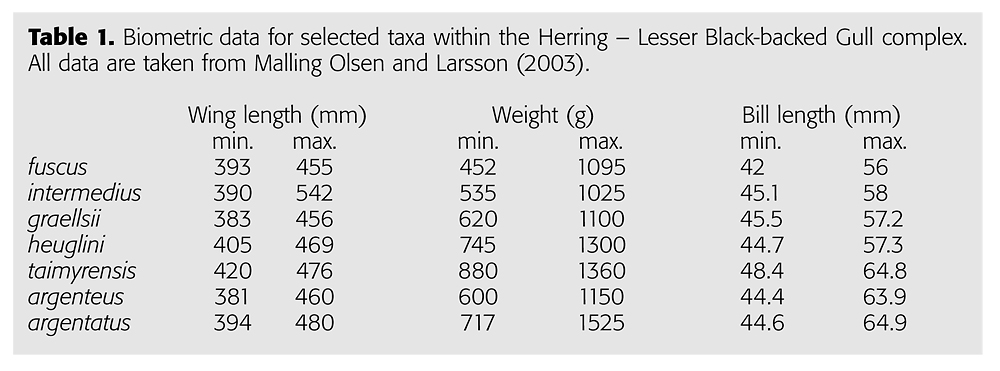

Grant as being "much like heuglini". However, biometric data indicate that taimyrensis is

appreciably larger than heuglini, and in fact is larger than many Herring Gulls (Table 1).

Kennerley et al. (1995) and Garner (1997) separated wintering heuglini and taimyrensis

based on these differences in size and structure, as well as upperpart tone (as per Figure

1). Despite the field identification by these authors, the question of what 'taimyrensis'

represents is controversial. If heuglini is the western and taimyrensis the eastern subspecies

of Heuglin's Gull, then Heuglin's is an unusually variable species (evident from Figure 1 and

Table 1). However, much of this variability results from the classification of taimyrensis as

the eastern form of Heuglin's, since taimyrensis is both different to the 'statistical average'

heuglini and is itself highly variable. Yèsou (2002) uses the marked variability of taimyrensis

to argue that it does not exist as a taxon. To summarise his argument, Yèsou suggests that

'taimyrensis' comprises either birds from a hybrid zone between western heuglini and Vega

Gull L. vegae (as argued by earlier workers), or yellow-legged individuals that were identified

as taimyrensis but were actually either pure vegae or pure heuglini. Yèsou's argument is a logical interpretation of the extremely variable descriptions of taimyrensis given in the

literature. If correct, his argument helps simplify matters as it means that taimyrensis has no

taxonomic validity and so should be left out of the Heuglin's Gull equation. Thus, to

understand what Heuglin's Gull looks like, it is necessary only to consider the western birds

– heuglini. So what is known of the field characters of these birds?

The average western heuglini is larger than fuscus, intermedius and graellsii (Table 1).

While it is most similar in size to graellsii, the average bird has rather more elegant

proportions, typically appearing to have a smaller, sleeker head and a slimmer neck (e.g. HERE, HERE). Unfortunately there is marked individual variation in the absolute size and

relative structure of heuglini, such that overlap with the other taxa is extensive. Structurally,

some heuglini appear very similar to intermedius and female graellsii (HERE, HERE) while

others appear large and even hulking (HERE, HERE). A particularly small, delicate heuglini

seen in the UAE (March 2004) was very similar to fuscus. Conversely, some fuscus can be larger and more robust than some heuglini. Bill size and proportions are also

variable in heuglini, as evident in the images on the right hand side.

(ii) Field characters of adult heuglini

The average and range of upperpart tones shown by heuglini match almost exactly those

of graellsii (Figure 1). Like graellsii there is individual variation, such that the darkest

heuglini overlap with paler intermedius and the palest birds are only fractionally darker than

the darkest argentatus. Thus, heuglini does not have a diagnostic upperpart grey tone.

Usually heuglini is described as having a white mirror only on P10 (e.g. HERE); this is

unlike the average graellsii which has mirrors on both P9 and P10. Harris et al. (1996)

suggested that in heuglini the white mirror on P10 is smaller and further from the feather tip

than in graellsii. Eskelin and Pursiainen (1999) found that this was the case with most of the

heuglini they encountered. It is not unusual to find graellsii in which the P10 mirror is merged

with the spot at the feather tip to form an extensive white tip to the feather, unlike the pattern

described for typical heuglini. However, there is variability and overlap between these taxa in

the pattern of white in the primaries. For example, intermedius (probably female) usually has

only 1 mirror, while heuglini (probably male) can sometimes have two. Moreover, heuglini

can have a large mirror on P10, as shown by the bird in Plate 18 of Rauste (1999). The

implication of this overlap is discussed with respect to the case study birds.

Figure 1 in Buzun (2002) illustrates what is described as "the most common wingtip

pattern" in heuglini. The figure shows a bird with black on 8 primaries, with the black

extending as a complete band across P4 and to the outer web of P3. From the limited

published data available, it is clear that both heuglini and graellsii can have black on a

total of either 6, 7 or 8 primaries (heuglini data published in Panov and Monzikov, 2000;

graellsii data in Rauste (1999), given in Hario, in litt.). These data indicate that black on 7 primaries is the most frequent pattern in both taxa (58% of graellsii, 54% of heuglini),

but that a larger proportion of heuglini (23%) have black on 8 primaries than do graellsii

(18%). However, sample sizes are so small (n = 38 and 26 respectively) that this

apparent difference in the frequency of black on 8 primaries may not be representative;

in fact BWP states that 25% of graellsii have black on 8 primaries. Even if a larger

sample supported the values of 23% (heuglini) and 18% (graellsii), a bird with black

on 8 primaries is only fractionally more likely to be a heuglini than a graellsii. Clearly, a

measure of the number of primaries with black pigmentation does not provide a firm

basis for field identification. Note that in Malling Olsen and Larsson's book (2003), the

text describing the frequency of black on P4 in heuglini appears to be erroneous

(revised edition p 395). They state that "Less than 5% black markings on P4". This

implies that more than 95% of heuglini lack black on P4 and so have black on only 6

primaries (P10-5 inclusive). This is at odds with both the published literature (Rauste,

1999 and Panov and Monzikov, 2000) and personal observations.

As with the pattern of white in the wingtip, it is clear that there is much individual variation and overlap between taxa in the extent of black in the primaries. It is also apparent from differences in published values that larger samples are needed before we can be confident about the significance of small apparent differences between heuglini and graellsii. The problem that individual birds can show differences between their right and left wing should also be borne in mind when using primary pattern to help identify individual birds; indeed, Plate 562 in Malling Olsen and Larsson (2003) shows one such graellsii. Unpublished studies also continue to show that the extent of white in the wingtip of British graellsii varies with age (adult birds continue to develop more white as they get older) and with sex (males typically have more white than females). While on average heuglini shows more black and less white in the wingtip than graellsii (Rauste, 1999), overlap with graellsii and intermedius is extensive. Adult heuglini have a greater tendency to have dark marks on the primary coverts (visible HERE) but as with other features, frequency statistics are needed before its value in field identification can be assessed.

In general terms, the bare part colouration of adult heuglini is similar to other Lesser Blackbacked

Gull taxa: legs are typically yellow, the bill bright yellow with a red gonys spot and

the orbital ring is red. Some gull species (e.g. cachinnans) have dark iris spotting

('peppering') such that in the field their eyes can look dark. The dark-eyed appearance of

some heuglini has been mentioned by several authors (e.g. Lindholm,1997) and this has

been suggested as something that might be useful for separating heuglini from graellsii and intermedius. However, data do not support the use of this feature. Rauste (1999)

found that around 10% of adult heuglini have eyes which have brown iris peppering but

analysis of unpublished data collected by Mars Muusse (n = 137) indicates that a very

similar proportion (11%) of graellsii also have some degree of iris spotting.

END OF PART 2

Heuglini adult HT-168224, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult HT-168224, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini adult, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 17 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 21 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 21 2006, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. AE4F0324 Ashdod 8.4.11.jpg) Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 08 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov.

Heuglini

adult, April 01 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen. Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.

Heuglini adult, April 06 2008, Tampere, Finland. Picture: Hannu Koskinen.