Thayer's Gull (thayeri)

Thayer's Gull (thayeri)

(last update: January 22, 2013)

Thayer's Gull 4cy (3rd basic moult) / sub-adult July

Interbreeding of Thayer’s Gull, Larus thayeri, and Kumlien’s Gull, Larus glaucoides kumlieni, on Southampton Island, Northwest Territories

A. J. GASTON and R. DECKER

IN: Canadian Field-Naturalist 99(2): 257-259

Gulls with the characteristics of Thayer’s and Kumlien’s gulls, Larus thayeri and Larus glaucoides kumlieni were found apparently interbreeding at a colony on Bell Peninsula, eastern Southhampton Island. The taxonomic status of L. thayeri may require revaluation.

Thayer’s Gull, Larus thayeri, breeds from Banks Island to Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic archipelago and as far south as Southampton and Coats Islands in Hudson Bay. Originally considered a race of the Herring Gull, Larus argentatus, (Dwight 1917), Thayer’s Gull was shown by Macpherson (1961) and Smith (1969) to be specifically distinct from that species. Kumlien’s Gull. L. glaucoides kumlieni, is confined to south and Cast Baffin Island and the northwest tip of the Ungava Peninsula (Smith 1969; A. O. U. 1957). Macpherson (1961) considered Thayer’s and Kumlien’s Gulls to be conspecific but Smith (1969) found no natural hybridization between the two forms in an area of sympatry at Home Bay, eastern Baffin Island.

In eastern Baffin Island the two species could be distinguished on the basis of wing-tip coloration (dark in Thayer’s, pale in Kumlien’s) and iris colour (speckled purple in Thayer’s, yellow in Kumlien`s). According to Smith, although both species are very variable, Thayer’s Gulls throughout their range always have extensive areas of black or brown pigmentation at the tips of the five longest primaries and at least some pigmentation in the iris, whereas typical Kumlien’s Gulls have the dark pigmentation in the wing-tips only on the outer webs and frequently have clear yellow irides. The wing-tips of Kumlien’s Gulls are never darker than medium grey. In both species the eye-ring is normally reddish-purple.

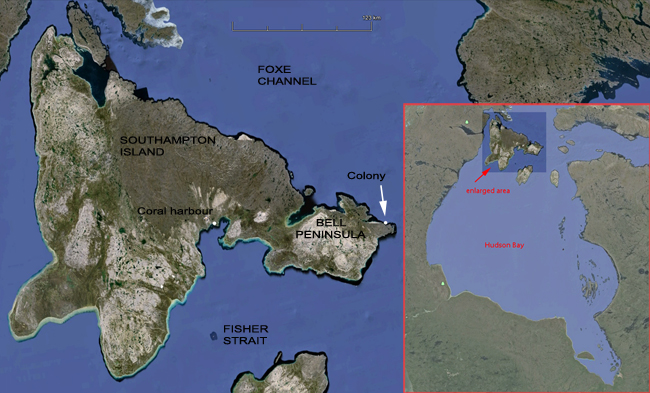

FIGURE 1. Southampton Island, showing the position of the colony visited (Colony)

In the course of seabird colony surveys around Southampton Island in June 1983 we located a mixed colony of Thayer’s and Kumlien’s Gulls on the northeast coast of the Bell Peninsula (Figure 1). That colony was not visited by Smith. We visited the colony on the ground on 29 June and estimated that 90-100 birds were present, many of which were incubating. The nests were situated on cliffs about 80 m high, facing seaward, but we were able to climb close to the colony and examine birds through binoculars at ranges down to 10 m. We made field notes of plumage and soft parts for all individuals we could see clearly and recorded where courtship or greeting behaviour suggested that birds were paired.

Plumages exhibited among birds seen well ranged from typical Thayer’s, with blackish tips to the primaries, enclosing prominent white windows, to typical Kum1ien’s, with virtually unmarked tips to the primaries, merely faint traces of pale brown on the outer web. At least two individuals appeared intermediate, with medium brown markings on the primaries distributed in exactly the same fashion as the typical Thayer’s. The pattern on the primary feathers was recorded for 43 birds, of which 25 (58%) appeared typical Thayer’s and 16 (37%) typical Kumlien’s.

All the birds present had dark eye-rings. Some had dark (presumably purple, Smith 1969) irides, while others had yellow irides and some appeared intermediate. No correlation was apparent between the colour of the primaries and the irides; birds with both Thayer’s and Kumlien’s wing patterns had yellow and dark irides. The two intermediate birds both had dark irides, as did 18 out of 24 (75%) birds seen adequately.

Plumage was satisfactorily described for twelve apparently mated pairs, of which all but two were incubating. Of that sample, 17 individuals were Thayer’s and 7 Kumlien’s, forming six pairs of Thayer’s/Thayer’s, five of Thayer’s/Kumlien’s and one Kumlien’s/Kumlien`s. That is close to the ratio predicted by an assumption of random pairing between the two species (50% T/T : 40% T/K : 10% K/K).

Our observations differed from those of Smith at Home Bay in showing a lack of assortative mating between the two species. It is also interesting to note that the proportion of birds with dark irides was 75%, similar to the proportion of Kumlien’s Gulls with dark irides recorded by Smith in southwest Baffin Island; the nearest population of Kumlien’s Gulls to eastern Southampton Island.

above: Bell Peninsula, Southampton Island. Picture: Timothy K.

Several possible explanations may reconcile our observations with those of Smith (1969):

(1) the “Kumlien’s Gulls” that were observed were actually unusually pale-winged Thayer’s Gulls;

(2) the mixed pairs that we observed were an unusual phenomenon not typical of the colony;

(3) species isolating mechanisms between these two “species" have recently begun to break down; or

(4) Thayer’s and Kumlien’s Gulls interbreed without assortment on eastern Southampton Island.

All of the first three explanations invoke statistically unlikely events and the fourth seems the most parsimonious. Smith noted that, among Thayer’s and Kumlien’s Gulls, there is a positive correlation between iris pigmentation and the amount of pigment in the primaries. Kumlien’s gull is extremely variable, with birds ranging from those with all white primary tips, as in the nominate L. g. glaucoides of Greenland, to those similar to the “intermediate" birds we describe here. According to Smith, the more pigmented phenotype becomes more common from northeast to southwest through the species range. If that is so, it is easy to see that the two forms might interbreed freely in the small area of sympatry on eastern Southampton Island, where the phenotypes are least distinct. The majority of Kumlien’s Gulls at Digges Sound, the most southwesterly part of the species’ range and 200 km southeast of Southampton Island, have dark irides (Gaston unpublished). If Smith’s contention that iris and eye-ring colour and contrast are the most important characters allowing interspecific segregation among arctic gulls is correct then, with Kumlien’s and Thayer`s Gulls in the northern Hudson Bay area overlapping extensively in this character, interbreeding is hardly surprising. A single Thayer’s Gull was paired with a Kumlien’s Gull at Digges Sound in 1980 and 1981 (Gaston unpublished).

If our explanation for the observed lack of mating preferences among Thayer’s and Kumlien’s Gulls in an area of sympatry is correct, what implications does it have for taxonomy? The two species interbreed in one part of their range, but apparently remain distinct at another. The situation may be analogous, on a small scale, to the subspecies rings described for the Herring Gull and other species by Mayr (1963). Our observations tend to support Weber’s (1981) suggestion that Kumlien’s and Thayer’s Gulls are conspecific. However, further field research will be necessary before a definitive statement on their taxonomy can be made.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hugh Boyd, Graham Cooch and W. Earl Godfrey for comments on this manuscript.

Literature Cited

American Ornithologists Union. l957. The A.O.U. Checklist of North American Birds. Fifth Edition. American Ornithologists Union.

Dwight, J. 1917. The status of “Larus thayeri, Thayer`s Gull". Auk 34: 413-414.

Mayr, E. 1963. Animal Species and Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K. 781 pp.

Macpherson, A. H. 1961. Observations on Canadian arctic Larus gulls, and on the taxonomy of L. thayeri, Brooks. Arctic Institute of North America Technical Paper Number 7. 40 pp.

Smith, N. G. 1969. Evolution of some arctic gulls (Larus): an experimental study of isolating mechanisms. A.O.U. Monograph Number 4. 99 pp.

Weber, J. W. 1981. The Larus gulls of the Pacific Northwest’s interior, with taxonomic comments on several forms (Part 1). Continental Birdlife 2: 1-10.

above: Coral Harbour on Southampton Island. Picture: Timothy K.