Thayer's Gull (thayeri)

Thayer's Gull (thayeri)

(last update: January 22, 2013)

Thayer's Gull 4cy (3rd basic moult) / sub-adult June

Below you will find a description of Chapter 36 THAYER'S GULL Larus thayeri, as published in one of the best Gull publication: "Gulls of the Americas" by Steve Howell & Jon Dunn.

"we" in the text below refers to the original authors. If any errors occur in this text, please let me know and mail to marsmuusseatgmaildotcom.

PART 1: IDENTIFICATION SUMMARY & TAXONOMY

PART 2: FIELD IDENTIFICATION SIMILAR SPECIES - ADULT

PART 3: FIELD IDENTIFICATION SIMILAR SPECIES - 1ST CYCLE

PART 4: FIELD IDENTIFICATION SIMILAR SPECIES - 2ND CYCLE

PART 5: RARER SPECIES

PART 6: DESCRIPTION AND MOLT - ADULT & 1ST CYCLE

PART 7: DESCRIPTION AND MOLT - 2ND & 3RD CYCLE

BELOW: PART 1

THAYER'S GULL Larus thayeri

Length 19.7-25 IN (50-63.5 cm)

IDENTIFICATION SUMMARY

A medium-large, dark-winged, pink-legged gull breeding in the Canadian High Arctic and wintering mainly along the N. American Pacific Coast. Bill relatively slender and parallel

edged with moderate gonydeal expansion. Adult has pale gray upperparts (Kodak 5-6) with slaty blackish wingtips (typically with white mirrors or mirror-tongues on P9-P10, distinct white tongue-tips on P6-P8) and, in basic plumage, extensive dusky mottling and streaking on head and neck. Juvenile medium-dark brown overall with blackish brown wing-tips and tail, pale inner webs to outer primaries. PA1 variable, starting Nov.-Apr. Subsequent ages variable in appearance. All ages have pink legs, often bright; adult eyes brownish to pale lemon, orbital ring purplish pink.

A medium-large, dark-winged, pink-legged gull breeding in the Canadian High Arctic and wintering mainly along the N. American Pacific Coast. Bill relatively slender and parallel

edged with moderate gonydeal expansion. Adult has pale gray upperparts (Kodak 5-6) with slaty blackish wingtips (typically with white mirrors or mirror-tongues on P9-P10, distinct white tongue-tips on P6-P8) and, in basic plumage, extensive dusky mottling and streaking on head and neck. Juvenile medium-dark brown overall with blackish brown wing-tips and tail, pale inner webs to outer primaries. PA1 variable, starting Nov.-Apr. Subsequent ages variable in appearance. All ages have pink legs, often bright; adult eyes brownish to pale lemon, orbital ring purplish pink.

Most likely to be confused with American Herring Gull, hybrid Glaucous-winged x American Herring and Glaucous-winged x Western gulls, and dark-winged Kumlien’s Gulls. Adult Thayer’s distinguished from American Herring Gull by average smaller size and more slender bill, eye color (rarely staring pale lemon like Herring), purplish pink orbital ring, slightly darker upperparts, and wingtip pattern: wingtips are slaty blackish (versus black) mainly on the outer webs so underwing looks silvery gray (not as extensively black as Herring) with blackish restricted to subterminal bands on the outer primaries; wingtips also have more-extensive white than typical of Herring Gulls in the West. Hybrids, however, can show these Thayer’s Gull plumage characters and are best identified by structure (especially bill size and shape). Dark-winged Kumlien’s Gull similar to Thayer’s Gull: Note that Kumlien’s averages paler gray above with slaty gray versus slaty blackish wingtips. See Similar Species Section for more detailed identification criteria and separation from various hybrid combinations, all of which are larger and bigger billed than Thayer’s.

First-cycle Thayer’s Gull identified by size and structure (especially bill), blackish brown to dark brown outer primaries with dark outer webs and pale inner webs. Thayer’s plumage characters can be shown by hybrids, however, so note size and structure relative to other gulls. Distinguished from Glaucous-winged and most Kumlien’s Gulls by dark brown primaries contrastingly darker than rest of upperparts, at least in fresh plumage. See Similar Species section for details.

TAXONOMY

Thayer’s Gull was described as a species [Brooks 1915], then lumped as a subspecies of Herring Gull based on perceived plumage intergradation in museum specimens. [AOU 1931; Dwight 1917] Macpherson [1961] showed that Herring and Thayer’s bred sympatrically without interbreeding and restored Thayer’s Gull to a full species while noting its similarity in several respects to Iceland and Kumlien’s Gulls. Subsequent authors have treated Thayer’s Gull as a full species [AOU 1973; AOU 1998; Browning 2002; Howell & Elliott 2001] or as a subspecies of Iceland Gull. [BOU 1991; Godfrey 1986] Studies on the breeding grounds where Thayer’s and Kumlien’s presumably interbreed have either: 1) been spurious [Smith 1966; Snell 1989; Snell 1991] or 2) failed to define the characters of the taxa, [Gaston & Decker 1985; Snell 1989; Snell 2002] so the degree of putative interbreeding is impossible to assess. Hence, we can’t learn how much Thayer’s and Kumlien’s interbreed until we can distinguish them, but we can’t distinguish them because they appear to interbreed. Field characters of adults based on wintering populations were proposed recently, [Howell & Elliott

2001] but critical studies on the breeding grounds are still needed.

STATUS & DISTRIBUTION

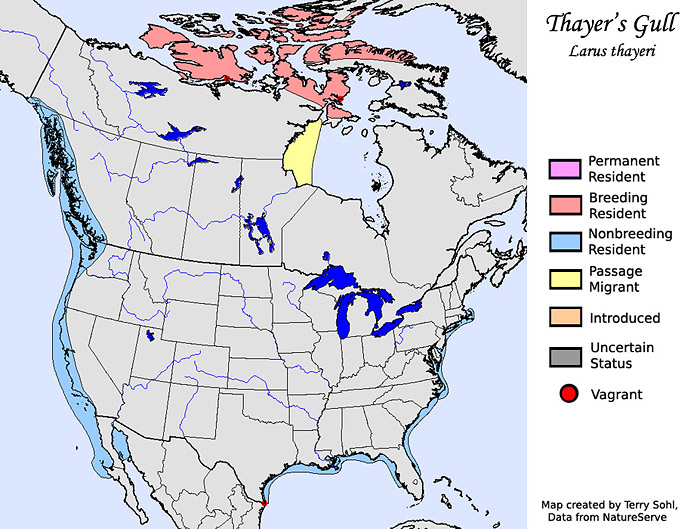

Breeds n. Canada, winters w. N. America. Vagrants reported from Japan and w. Europe.

Breeds n. Canada, winters w. N. America. Vagrants reported from Japan and w. Europe.

Breeding. Breeds (June-Aug.) in Arctic Canada from Banks Is. and s. Victoria Is. east to Southampton Is., Ellesmere Is., Devon Is., and e.-cen. Baffin Is., and on Arctic coast of Keewatin; has also bred nw. Greenland.

Nonbreeding. Southbound fall movement evident in sw. Hudson Bay and s. Yukon by early Aug. (peak movements early-mid-Sept.), in se. Alaska by late Aug. (peak movements mid-late Sept.). Uncommon fall migrant (mainly Aug.-Sept.) along Arctic coast of Alaska west to Point Barrow and casual in Bering Sea. On Pacific Coast, arrival in the Northwest may be as early as late Aug., but mostly mid-Oct. – Nov. In coastal Calif., a few arrive mid-late Oct., most during Nov. A juvenile reported from Salton Sea, 29 Sept.,[ Patten et al. 2003] if correct, would be remarkable. In interior East and Great Lakes region, first fall arrivals typically mid-Oct., more often late Oct.-early Nov., exceptionally late Sept. From n. interior regions (for example, Prairie Provinces) most birds depart by late Nov. Migration route to Pacific Coast from Arctic breeding grounds unclear, perhaps a direct overland flight through Yukon and B.C. at high elevation.

Locally fairly common in winter (mainly Oct./Nov.-Mar./Apr.) from se. Alaska south along coast (fewer to inland valleys and reservoirs) to cen. Calif., rarely north to s. coastal Alaska (Kodiak Is.), rarely to uncommonly (mainly Dec.-Mar.) south to Baja Calif., casually to Baja Calif. Sur. Casual (late Sept.-May mostly fall) in cen. and e. Aleutians. Small numbers also winter Salton Sea and n. Gulf of Calif., Mex.; casual in the Southwest. Bare in Great Basin, Great Plains. and Mid-west, especially Great Lakes region (where more numerous on w. lakes; for example. outnumbers Kumlien’s more than 3:1 on Indiana lakefront[Brock 1997]), but also on lower Ohio and Miss. rivers and nearby large lakes. Rare to very rare south to Gulf of Mex. coast in Tex., casually south to n. Tamaulipas, Mex. [Gee & Edwards 2000] and east to Fla. Very rare to casual along Atlantic Coast of N. America (mainly Nov./Dec.-Mar.), with perhaps most records from Mid-Atlantic region, but also reported north to Nfld.[ Peters & Burleigh 1951]; south to Fla.

Spring movement evident in U.S. by Feb.: most depart wintering areas during Mar.-early Apr.; some remain into late Apr., very few into May. At least in some years, thousands of birds stage early-mid-May in se. Alaska (around Juneau), presumably before a direct overland flight to Arctic coast. [Tobish 1996] Common on SW. Hudson Bay late May-mid-June (some nonbreeders remain through summer). First arrivals on breeding grounds mid-late May, most not until June. Casual in winter range June – Aug., with exceptional summer records as far south as s. Calif. And Fla.