Larus cachinnans

Larus cachinnans

(last update:

Greg Neubauer

Marcin Przymencki

Albert de Jong

Mars Muusse

In 2010, Chris Gibbins, Brian J. Small and John Sweeney published two extensive papers in Britsih Birds, dealing with Caspian Gull. Below, you will find the content of the first paper "Part 1: typical birds".

The full title reads: From the Rarities Committee's files - Identification of Caspian Gull. Part 1: typical birds, by Chris Gibbins, Brian J. Small and John Sweeney, IN: BB 103/2010. ORDER PAPER COPY!

"we" in the text below refers to the original authors. If any errors occur in this text, please let me know and mail to marsmuusseatgmaildotcom.

Identification of Caspian Gull. Part 1: typical birds

Abstract

This paper deals with the identification of the Caspian Gull Larus

cachinnans. The aim is to synthesise what is currently known about the

identification of this species and discuss the appearance of proven and suspected

hybrids. The paper is split into two parts. Part 1 deals with the identification of

typical cachinnans and their separation from Herring L. argentatus and Yellow-legged L. michahellis Gulls. It is targeted at non-specialists who remain unsure of the most

reliable identification criteria, and at local records committees who need a

structured basis for assessing claims. The paper covers all age groups, but

concentrates particularly on those treated in less detail in the published literature. It includes a summary table that distils key information and ranks criteria

according to their value in field identification. Part 2, to be published in a future

issue, will deal with the identification of less typical individuals and hybrids.

Introduction

A lone Caspian Gull rests with a group of Herring Gulls in the Netherlands (January 09 2012, Utrecht, picture: Herman Bouman). Can you see it? It is white-headed, dark-eyed and is

holding its bill distinctly downwards.

Below: Larus cachinnans adult, 29 December 2011, Boulogne-sur-Mer, NW France, Picture: Jean-Michel Sauvage. White-headed bird in the centre.

Rationale and aim

Our perception of the Caspian Gull Larus

cachinnans as a British bird has changed dramatically

in the past 20 years. It has gone

from being a poorly known, southeastern

race of Herring Gull L. argentatus (Grant 1986) to being recognised as a valid species

(Leibers et al. 2001; Collinson et al. 2008)

that regularly occurs in Britain. This transformation

has been due, in no small part, to

the groundbreaking identification studies of Klein (1994), Gruber (1995), Garner (1997),

Garner & Quinn (1997) and Jonsson (1998). Subsequent contributions (e.g. Bakker et al.

2000, Small 2000, Gibbins 2003) built on this

pioneering work. Along with that of Malling

Olsen & Larsson (2003), these studies have

demystified this gull to the extent that its identification may now be considered rather

passé by some birders. But can we really close

the book on the identification of cachinnans?

An identification review is timely, given

that BBRC has now passed assessment of

post-1999 claims to local committees. Moreover,

there is anecdotal evidence that many

observers are still struggling with the identification

of Caspian Gull. Understandably, this

is chiefly the case in areas where cachinnans remains truly rare and where observers have

had little chance to gain first-hand experience.

The key problems are confusion over

the most reliable identification features and a

failure to appreciate fully the normal variability shown by cachinnans and similar taxa.

Some identification problems merely reflect

the extremes of variation shown by cachinnans;

others stem from hybrids, originating

from the mixed-species colonies in central

Europe (Neubauer et al. 2009); and some

problems may occur with birds that have no cachinnans genes but which represent the

extremes of variation in other species. We

have arrived at a point where we should take

stock of what we know of the identification

of typical cachinnans and begin to look more

closely at the identification of less typical

individuals and their separation from

hybrids. Are there clear dividing lines, and if

so where are they?

The aim of this paper is to provide a distillation

of known criteria, assess their merits

and, for the first time, discuss the identification of less typical and hybrid individuals.

We hope that it will be of value to both birders and local records committees. Part 1

deals with typical individuals. We describe in

detail the plumage and structure of typical

birds, emphasising key average differences

from Herring Gull and Yellow-legged Gull L.

michahellis; we outline normal variation but

leave the extremes aside. Appendix 1 summarises

key distinctions between typical cachinnans, michahellis and Herring Gull and

ranks criteria according to their relative

importance. It should not be used in isolation,

but as a convenient summary and as an

entry point to the details in the text. Less

typical and extreme individuals will be dealt

with in part 2, where we shall also discuss the

identification of hybrids; this will be published

in a future issue.

To date, literature on cachinnans has

tended to focus on one or two age groups– the first-winter and adult birds that are

found most regularly in Britain. To redress

this balance, we pay particular attention to

other age groups. The paper is intended primarily

for birders in Britain, so does not

discuss Heuglin's Gull L. fuscus heuglini. This

taxon can look remarkably cachinnans-like in

structure and some immature plumages. However, serious confusion is unlikely: heuglini has a different call, dark inner firstgeneration

primaries, and once adult-type

grey feathers develop their tone is much

darker than those of cachinnans.

Circularity and the empirical basis

of this paper

Circular reasoning (bird A is a Caspian Gull,

it shows features X, Y and Z, therefore X, Y

and Z are features of Caspian Gull) may

undermine attempts to develop identification

criteria. Circularity can be avoided if:

(a) the

species is studied in the core of its accepted

breeding range, where potential confusion

species are absent and hybridisation is not a

significant issue; or

(b) the sample consists

only of individuals of known provenance

(ringed birds). Much of our knowledge of cachinnans is actually based on unringed

birds observed in western Europe in winter,

well away from core breeding areas and on

the edge of the wintering range.

Circularity is

thus a potential problem, especially because of the risk of incorporating an unknown number of hybrids into the 'cachinnans' sample. Moreover, as we may be picking up

only the most striking birds in Europe, there

is a danger of developing criteria based on an

unrepresentative sample. Studies of cachinnans wintering in the Middle East suffer

similar problems, owing to the presence of

extremely similar taxa whose identification

has yet to be fully resolved (notably barabensis). Access to the heart of the breeding range of cachinnans, where both

Herring and Yellow-legged Gulls are absent,

is difficult and few western ornithologists

have studied the species there. Consequently,

we are largely constrained to studying cachinnans in wintering areas and must be aware of

the problem of circular reasoning.

Circularity is most problematic with less

typical individuals. In part 2 we therefore use

ringed individuals of known provenance to

help to develop criteria for the separation of

hybrid from pure individuals. Circularity is

less of an issue with the 'classic' birds that are

the focus of part 1. Nonetheless, to study cachinnans we have travelled to parts of the

breeding range (e.g. several trips to the

Danube Delta, Romania) and areas of the

southern Baltic where cachinnans occurs in

large numbers in the immediate postbreeding

period and can be the most abundant

large gull at some localities (e.g. on the

Curonian Spit in Lithuania). The majority of plates show birds from these areas. Since the

paper is aimed at British birders, it may seem

that examples of cachinnans photographed in

Britain are under-represented in the plates;

this is a product of the need to limit the

problems of circularity.

'Herring Gull' is used here to refer collectively

to both races; 'argentatus' is used when

referring specifically to the Scandinavian/

Baltic race and 'argenteus' when referring to

the British/west European race. Yellow-legged

Gull is referred to as 'michahellis' and relates

only to Mediterranean birds. The Atlantic

Island populations of Yellow-legged Gull represent

a taxon whose status is still debatable

and which, in any case, have rather dark

immature plumages and structural traits that

make them unlikely to be confused with cachinnans. We treat cachinnans as monotypic,

as the extent and nature of geographic

plumage variation has yet to be firmly established.

Nonetheless, future work may reveal

consistent differences between eastern and

western birds (see section on adults).

Patterns of occurrence in Britain

It is difficult to assess the number of cachinnans currently occurring in Britain each year.

This relates chiefly

to the fact that the

species is now so

abundant in some

areas that observers

do not necessarily

report all sightings.

Nonetheless, it is

clear that cachinnans is recorded

more frequently

now than in the past

and that there are

strong seasonal and

geographic patterns

to its occurrence.

Caspian Gulls are

most frequent in southern England,

particularly the

southeast. The first

birds arrive in late summer and early autumn, when the

majority of records come from the coastline

between Kent and Suffolk. Juvenile cachinnans now occur regularly in early August,

when many young British Herring Gulls are

not even fully independent. These cachinnans are not necessarily from the nearest breeding

areas, since juveniles may disperse far from

their natal colony soon after reaching independence.

For example, a bird at Espoo,

Finland, on 26th July 2004 had been ringed

as a pullus on 27th May on the River Dnper

in southern Ukraine (49°46'N 31°28'E). Consequently,

observers should be looking out

for first-calendar-year (1CY) cachinnans from late July onwards. Post-breeding adults

tend not to be seen in Britain until later in

the autumn; this delayed arrival may be

linked to the progression of primary moult.

Following their arrival, many birds move

inland and disperse northwards as the

autumn and winter progress. They are supplemented

by new arrivals, perhaps linked to

cold weather on the Continent. For example, hundreds of cachinnans are present at

lagoons along the coast of Lithuania in autumn but these disappear in midwinter,

once the water freezes (Vytautas Pareigis

pers. comm.). The largest numbers of cachinnans in Britain are recorded in winter, with

birds seen regularly on favoured landfill sites

and in reservoir roosts in southern and

central England. However, they remain distinctly

scarce in north and northwest Britain;

there are few records north of the River Tees

and the species remains extremely rare in

Scotland (fewer than five records) and

Ireland. Very few are recorded in the summer

months. This probably reflects the movement

of birds back to the Continent, but perhaps

also the relative difficulty of identifying

moulting immatures in summer and the fact

that gull-watching in Britain tends to be a

winter pursuit.

Identification

Classic structure: long exposed tibia, high breasted, elongated rear end, snouty head.

Size and structure

Caspian Gulls can be strikingly large, tall

birds, but most individuals are similar in

length and weight to Herring Gull and so do

not stand out on size alone. However, cachinnans is structurally distinctive at all ages, often described as 'lanky' or 'gangly'. It has

relatively long, thin-looking legs (the extra

length is particularly noticeable in the tibia)

and often seems to stand taller than Herring

Gull. Next to michahellis, its legs tend to look

longer and less robust. However, some michahellis are long-legged compared with

Herring Gulls, so observers should be

mindful of this when confronted with an

apparently lanky bird. There are marked differences

in size and structure between male

and female cachinnans (see Malling Olsen &

Larsson 2003) and these differences may be

more marked than for other large gulls

(Gibbins 2003). Some, presumably males, can

look incredibly long-legged, yet others, presumably

females, can actually look rather

short-legged. Consequently, birders and committees

should not automatically dismiss a

bird that lacks the textbook long-legged look.

=================================================

| TARSUS | range | average | n: |

| L.a. argentatus | |||

| adult male | 62.0-75.2 | 67.1 | 131 |

| adult female | 55.1-69.8 | 62.4 | 142 |

| first-year male | 59.4-70.3 | 66.7 | 48 |

| first-year female | 55.8-68.0 | 60.9 | 43 |

| L.a. argenteus | |||

| adult male | 56.4-70.3 | 64.1 | 52 |

| adult female | 53.3-68.6 | 59.6 | 63 |

| first-year male | 54.5-66.7 | 62.6 | 22 |

| first-year female | 52.9-64.2 | 58.5 | 22 |

| TARSUS (N Norway) | |||

| adult male | 62.5-75.0 | 67.5 | 25 |

| adult female | 57.1-68.1 | 62.2 | 21 |

| TARSUS (Finland. Estonia) | |||

| adult male | 67.0-72.0 | 69.2 | 6 |

| adult female | 57.3-66.8 | 60.6 | 7 |

| TARSUS (Denmark) | |||

| adult male | 61.6-73.6 | 66.7 | 52 |

| adult female | 53.6-70.4 | 62.8 | 55 |

| TARSUS (W Germany) | |||

| adult male | 57.0-72.0 | 65.9 | 80 |

| adult female | 52.5-67.0 | 61.2 | 80 |

| TARSUS (Sobortsk, White Sea) | |||

| - | 58.8-75.0 (rarely <70mm) | ||

| L.c. cachinnans | |||

| adult male | 65.8-77.0 | 69.9 | 30 |

| adult female | 58.7-73.8 | 64.0 | 26 |

| first-year male | 65.7-69.9 | 67.5 | 4 |

| first-year female | 57.2-66.1 | 61.1 | 4 |

The head can appear oddly small for the

body, generally looks pear-shaped, and normally

lacks the bulky feel of the head of

Herring Gull and (especially) michahellis.

The head often looks 'anorexic', as though

there is little flesh covering the skull; this

means that head shape equates more closely

to skull shape than for other large gulls. The

often-quoted, but perhaps over-emphasised,

'snouty' look is due to a combination of the

long sloping forehead and the relatively long,

slim bill, which gives the front of the head a

tapering, 'pulled-out' appearance. This

snouty look can be a striking and defining

feature, but it is important to note that not

all cachinnans show it. For a significant proportion

of (presumed) females, the bill

length is unremarkable, and, because of their

higher, more rounded heads, they may recall

Common Gull L. canus. Conversely, some

larger males can have a robust bill and a

solid, more angular head that overlaps in appearance with both Herring and Yellow-legged

Gulls. Yellow-legged Gulls typically

have a deeper, blunter bill and a larger, more

angular head, yet, as with other gulls, males

and females can be rather different, and the1

slighter individuals overlap with Herring and

even Lesser Black-backed Gulls L. fuscus. Furthermore, michahellis from the Atlantic coast

of the Iberian Peninsula tend to be smaller,

less robust and less rangy than Mediterranean

birds.

Most Caspian Gulls appear longer-billed

than Herring Gull and michahellis. They have

a more gentle, even curve to the culmen and

a less obvious gonydeal angle; unlike Herring

Gull and michahellis there is little or no

bulging at the gonys and the general impression

is of a gently tapering bill. Data in

Malling Olsen & Larsson (2003) indicate that

there is actually much overlap in the bill

length of cachinnans and Herring Gull

Most Caspian Gulls appear longer-billed

than Herring Gull and michahellis. They have

a more gentle, even curve to the culmen and

a less obvious gonydeal angle; unlike Herring

Gull and michahellis there is little or no

bulging at the gonys and the general impression

is of a gently tapering bill. Data in

Malling Olsen & Larsson (2003) indicate that

there is actually much overlap in the bill

length of cachinnans and Herring Gull

(males: Herring 46.4–64.9 mm, mean 54.6, cachinnans 50.7–63.5 mm, mean 56.3;

females: Herring 44.9–59.0 mm, mean 49.7, cachinnans 48.0–59.5 mm, mean 51.9). Thus,

the longer-billed impression given by cachinnans results from the interaction of its shape,

depth and length, accentuated in some birds

by the pear-shaped head and long neck.

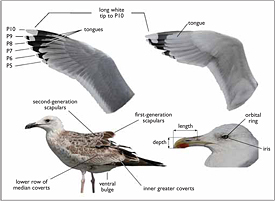

Gibbins (2003) assessed the ratio between

bill length and gonys depth (measured from

photographs; length and depth as indicated

in fig. 1) in a sample of Herring and Caspian

Gulls (n = 68). Most Herring Gulls were

scored as having a ratio of 1.75–2.00 whereas

most cachinnans were scored as 2.25–2.50.

Thus for cachinnans the bill is most often

more than twice as long as its maximum

depth, while for Herring it is most frequently

a little less than twice its maximum depth.

Some cachinnans can be extremely long- and

slim-billed, with ratios up to 3.25, compared

with a maximum of 2.5 in Herring. Note that

bill deformity is not uncommon among gulls

(especially first-years), so a long, slim bill is

not, in itself, sufficient for identification or

record acceptance.

The body shape of cachinnans is subtly

distinctive. One of the most noticeable features

is the attenuated rear end; this is a consequence

of a flat back, limited or absent

tertial step and relatively long wings. The tip of the tail falls one-third to halfway along the

exposed primaries, while on Herring Gull it

usually reaches halfway or slightly further

(this comparison holds good only for birds

that are not moulting their outer primaries).

Herring Gulls and michahellis are generally

less attenuated and have a more prominent

tertial step although, especially in hot

weather, michahellis can appear to have a very

long rear end. The belly profile of cachinnans often continues behind the legs as a ventral

bulge that sags below the wings, making the underbody resemble a boat keel in shape.

This may be obvious for some birds yet not

apparent for others. At rest, compared with

Herring Gull and most michahellis, cachinnans has a higher chest, with a slightly

'bosomed' effect, as if holding its breath. This

stance is exaggerated by the long wings and

ventral bulge, which, along with the head and

bill shape, give the most typical birds an

instantly recognisable jizz.

In flight, the long- and broad-winged

appearance of cachinnans may catch the eye

of regular gull-watchers. Compared with

Herring Gull and michahellis, the greater

length of the head, bill and neck extension in

front of the wings is also noticeable.

To summarise, the most typical cachinnans have a striking jizz, much more eyecatching

than that of michahellis. They can be

a large yet elegant gull, easily located in

mixed flocks. However, some lack the rangy/gangly/snouty character usually associated

with the species and so are much less

distinctive. Weather conditions and posture

influence appearance, and in hot conditions,

when their feathers are sleeked down, cachinnans may look very slim, long-legged and

lanky. On cold

winter days they

look quite different,

and experience

from birding

holidays in the

Middle East may

not translate well

to Britain.

Adult Caspian Gull, Latvia, 11 Apr 2009.This large male was typically

aggressive and, as pictured here, incessantly gave the rapid, laughing call which

is diagnostic of Caspian Gull. Unlike Yellow-legged and Herring, Caspian Gulls

hold their wings open when giving the long call – the so-called 'albatross

posture'.The characteristic primary pattern is visible here: note the grey

tongues eating into the black wing-tip on the upperside of P7–10 and the

long silvery tongue on the underside of P10. Like Yellow-legged Gull, Caspian usually has a broad, black subterminal band extending unbroken across P5,

but there is much individual variation and this bird has only isolated black

marks on the outer and inner webs.

Behaviour and

voice

Caspian Gulls mix

freely with other

large gulls in both

feeding and resting

areas (plate 48).

When feeding on

rubbish dumps,

large individuals

are often extremely

aggressive (more so

than Herring and michahellis) and

dominate favoured

patches. Caspian Gulls habitually raise their wings, especially

in aggressive encounters, and this can be an

easy way to locate them in groups of feeding

gulls.

Their calls (appendix 1) also attract attention

and can be heard clearly even above the

noise created by large numbers of squabbling

Herring Gulls. The importance of the long

call and long-call posture in separating cachinnans from other large gulls has been

rather underplayed in the literature and it is

clear that not all birders are aware of their

value. Calls are always difficult to capture in

words and the long call of cachinnans has

been described in various ways. The full long

call is a loud, rapid 'haaa-haaa-haa-ha-ha-haha-

ha-ha-ha', with a characteristic nasal,

laughing quality, very different from Herring

Gull's. Once heard it is easily recognised.

Adults frequently give shorter versions of this

call (the last six or seven notes) during aggressive encounters. Evidence suggests that

the full long call takes time to develop: in

August and September, 1CY birds give a

much more subdued version (Hannu Koskinen,

pers. comm., CG pers. obs.). Juveniles

often also give screeching calls, especially when coming in to land to join a feeding

melee. These calls are very high-pitched (they

have a clear squealing quality) and, once

heard, are distinct from the whine of juvenile

Herring Gulls.

The full long call is frequently accompanied

by the 'albatross posture', with wings

open and held back and the head raised progressively

as the notes are delivered (plate

49). Herring Gulls and michahellis keep their wings closed when long-calling, so this is a

key distinction. Herring Gulls raise their

heads only to approximately 45° when longcalling,

while both cachinnans and michahellis often (but not always) raise them to

90°.

Urszulin (near Zabrodzie), Włodawa County, Lublin Voivodeship (51.4342N 23.2285E). Recorded on 2012-03-12 by: Jarek Matusiak. Colony about 32 Pairs; some birds can be hybrids among L. cachinans and L. michahellis. |

|

Góra Kalwaria (near Podłęcze), Piaseczno County, Masovian Voivodeship (52.0312N 21.2262E). Recorded on 2013-02-26 by: Jarek Matusiak. Response on White-tailed Eagle; colony of about 83 pairs; some birds can be hybrids among L. cachinnans and L. michahellis. At least 3 L. michahellis were present, and one L. f. intermedius (but silent). |

|

Rødvig havn (55.2528N 12.3737E). Recorded on 2009-10-31 by: Lars Krogh. Begging 1st winter bird. Background gulls are some L. argentatus and L. fuscus. |

END OF PART 1

Larus cachinnans 1CY UKK L-011765 August 13 2015, Simrishamn, Sweden.

Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.

Larus cachinnans 1CY UKK L-011765 August 13 2015, Simrishamn, Sweden.

Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo. Larus cachinnans 1CY HCL23 August 10 & October 10 2015, Kampen, the Netherlands & Kent, UK.

Picture: Cor Fikkert & Michael Southcott.

Larus cachinnans 1CY HCL23 August 10 & October 10 2015, Kampen, the Netherlands & Kent, UK.

Picture: Cor Fikkert & Michael Southcott.Ringed as pullus on May 20 2015 at Yavonov, Lviv Oblast, (westernmost) Ukraine.

Larus cachinnans 1CY & 3CY PANX August & October 2009, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany & December 2012, Herstal - Liege, Belgium.

Larus cachinnans 1CY & 3CY PANX August & October 2009, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany & December 2012, Herstal - Liege, Belgium. Larus cachinnans 1CY PAPP August 28 2009, Windheim - Minden, Germany (52°24'50N, 09°01'49E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PAPP August 28 2009, Windheim - Minden, Germany (52°24'50N, 09°01'49E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PDNZ July 25 2010, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PDNZ July 25 2010, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PHHL August 26 2011, Warnemünde - Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany (54.10N 12.05E). Picture: Ronald Klein.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PHHL August 26 2011, Warnemünde - Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany (54.10N 12.05E). Picture: Ronald Klein. Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PKSD August 2012 - June 2013, Minden & Dümmer, Germany.

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PKSD August 2012 - June 2013, Minden & Dümmer, Germany.

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PKTE August 17 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PKTE August 17 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PLAH August 21 2012, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PLAH August 21 2012, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PNDT August 30 2013, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PNDT August 30 2013, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PNNL August 2013-February 2014, England and France. Picture: Lee Gregory & Alasin Fossé.

Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PNNL August 2013-February 2014, England and France. Picture: Lee Gregory & Alasin Fossé.  Larus cachinnans PNXB 1CY & 3CY, August 2013 & December 12 2015, the Netherlands & UK. Picture: N. Huig & R. van Oosteroom & Michael Southcott.

Larus cachinnans PNXB 1CY & 3CY, August 2013 & December 12 2015, the Netherlands & UK. Picture: N. Huig & R. van Oosteroom & Michael Southcott. Larus cachinnans 1CY PSSN August 29 2011, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PSSN August 29 2011, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak. Larus cachinnans 1CY PUEA August 16 2010, Kolobrzeg, Poland. Picture: Ryszard Rudzionek.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PUEA August 16 2010, Kolobrzeg, Poland. Picture: Ryszard Rudzionek.  Larus cachinnans 1CY & 3CY PUHP 2010 & 2012, Miedwie lake, Poland, Simrishamn, Sweden & Friedrichshafen, Germany.

Larus cachinnans 1CY & 3CY PUHP 2010 & 2012, Miedwie lake, Poland, Simrishamn, Sweden & Friedrichshafen, Germany.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PUKZ August 18 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PUKZ August 18 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PUNP August & December 2010, Poland & Switzerland. Picture: Michal Rycak & Ernst Weiss.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PUNP August & December 2010, Poland & Switzerland. Picture: Michal Rycak & Ernst Weiss. Larus cachinnans 1CY PUST August 09 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PUST August 09 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PUTE August 09 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PUTE August 09 2010, Lubna, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.  Larus cachinnans 1cy PUTH August 09-10 2010, Rødvig-Stevns, Sjælland, Denmark. Picture: Lars Krogh.

Larus cachinnans 1cy PUTH August 09-10 2010, Rødvig-Stevns, Sjælland, Denmark. Picture: Lars Krogh.  Larus cachinnans 1CY 089P August 23 2006, Stroby ladeplads, Denmark & September 26 2006, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo & Lars Krogh.

Larus cachinnans 1CY 089P August 23 2006, Stroby ladeplads, Denmark & September 26 2006, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo & Lars Krogh.  Larus cachinnans 1CY 129P August 04 2006, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY 129P August 04 2006, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY 06P3 July 26-28 2014, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. Picture: Jeroen Breidenbach.

Larus cachinnans 1CY 06P3 July 26-28 2014, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. Picture: Jeroen Breidenbach.  Larus cachinnans 1CY 53P5 August 17 2015, IJmuiden, the Netherlands.

Larus cachinnans 1CY 53P5 August 17 2015, IJmuiden, the Netherlands. Larus cachinnans 67P6 1CY, August 24 2015, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Picture: Merijn Loeve.

Larus cachinnans 67P6 1CY, August 24 2015, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Picture: Merijn Loeve.  Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DA-07404 July 14 1999, Deponie Coerde - Münster, Germany (52.00.39N 07.38.48E). Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DA-07404 July 14 1999, Deponie Coerde - Münster, Germany (52.00.39N 07.38.48E). Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-24320 August 09 2007, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-24320 August 09 2007, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-25430 August - October 2011, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-25430 August - October 2011, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PLG DN-25866 2008 & 2009, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PLG DN-25866 2008 & 2009, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-28035 July 21 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Hans Larsson.

Larus cachinnans 1CY PLG DN-28035 July 21 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Hans Larsson. Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PLG DN-28100 August 2012 - April 2013, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch.

Larus cachinnans 1CY-2CY PLG DN-28100 August 2012 - April 2013, Deponie Pohlsche Heide - Minden, Germany (52°23'05N, 08°46'45E).

Picture: Armin Deutsch. Larus cachinnans 1CY 6L48 August 14 2015, Simrishamn, Sweden.

Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.

Larus cachinnans 1CY 6L48 August 14 2015, Simrishamn, Sweden.

Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.  Larus cachinnans 1CY XNCA August 30 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo.

Larus cachinnans 1CY XNCA August 30 2012, Simrishamn, Sweden. Picture: Jörgen Bernsmo..jpg) Larus cachinnans 1CY VL5S August 23 2011, Kerteminde, Denmark. Picture: Kjeld Tommy Pedersen ringing team.

Larus cachinnans 1CY VL5S August 23 2011, Kerteminde, Denmark. Picture: Kjeld Tommy Pedersen ringing team. Larus cachinnans 1CY SVS 90A71627 August & November 2010, Sweden & the Netherlands. Picture: Anders Åkesson & Ruud Altenburg.

Larus cachinnans 1CY SVS 90A71627 August & November 2010, Sweden & the Netherlands. Picture: Anders Åkesson & Ruud Altenburg. Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2008, Riga, Latvia. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2008, Riga, Latvia. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2008, Riga, Latvia. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2008, Riga, Latvia. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 23 2008, IJmuiden, the Netherlands. Picture: Mars Muusse.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 23 2008, IJmuiden, the Netherlands. Picture: Mars Muusse. Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 30 2007, Westkapelle, the Netherlands. Picture: Ies Meulmeester.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 30 2007, Westkapelle, the Netherlands. Picture: Ies Meulmeester. Larus cachinnans 1cy, 15 August 2012, Barneveld, the Netherlands. Picture: Herman Bouman.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, 15 August 2012, Barneveld, the Netherlands. Picture: Herman Bouman. Larus cachinnans 1cy, 25 July 2012, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Picture: Herman Bouman.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, 25 July 2012, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Picture: Herman Bouman.  Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2011, Gelendzjik, Kraj Krasnodar, Russia. Picture: Potatoes_Ru.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, August 2011, Gelendzjik, Kraj Krasnodar, Russia. Picture: Potatoes_Ru. Larus cachinnans 1CY, August 15 2012, Barneveld, the Netherlands. Picture: Maarten van Kleinwee.

Larus cachinnans 1CY, August 15 2012, Barneveld, the Netherlands. Picture: Maarten van Kleinwee. Larus cachinnans 1CY, July 29 2007, Karrebæksminde, Sjælland, Denmark. Picture: Lars Adler Krogh & Frank Abrahamson.

Larus cachinnans 1CY, July 29 2007, Karrebæksminde, Sjælland, Denmark. Picture: Lars Adler Krogh & Frank Abrahamson. Larus cachinnans 1CY, July 26 2010, Damhussøen - København, Denmark. Picture: Klaus Malling Olsen.

Larus cachinnans 1CY, July 26 2010, Damhussøen - København, Denmark. Picture: Klaus Malling Olsen.  Larus cachinnans 1CY, August 22 2007, Salthammer odde, Bornholm, Denmark. Picture: Sune Riis Sørensen.

Larus cachinnans 1CY, August 22 2007, Salthammer odde, Bornholm, Denmark. Picture: Sune Riis Sørensen.  Larus cachinnans 1cy, July 24 2013, Katwijk, the Netherlands.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, July 24 2013, Katwijk, the Netherlands. Larus cachinnans 1cy, July 24 2013, Katwijk, the Netherlands.

Larus cachinnans 1cy, July 24 2013, Katwijk, the Netherlands.