glaucoides & kumlieni

glaucoides & kumlieni

(last update: October 12, 2011)

Iceland & Kumlien's Gull adult February

In 2001 and 2003, two extensive papers appeared in the Finnish ornithological magazine "Alula", dealing with adult Thayer's Gull and adult Kumlien's Gull. Up to now, this is by far the most extensive research on Kumlien's, and anyone interested in this topic is encouraged to get a copy of this issue. Below, you will find the content of this paper, illustrated with many more images from both Newfoundland and Iceland.

The full title reads: Identification and Variation of Winter Adult Kumlien’s Gulls, by Steve N.G. Howell & Bruce Mactavish, IN: Alula 1/2003.

"we" in the text below refers to the original authors. If any errors occur in this text, please let me know and mail to marsmuusseatgmaildotcom.

Identification and Variation of Winter Adult Kumlien’s Gulls

Long ago, William Brewster (1883) described “an apparently new gull from eastern North America,” which he named Larus kumlieni - the “Lesser Glaucous-winged Gull." This taxon has since become known as Kumlien’s Gull and is usually treated as a subspecies of Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides), e.g. by Godfrey (1986) and AOU (1998). The relationship of Kumlien’s Gull and Iceland Gull to Thayer’s Gull, however, remains contentious, with the latter taxon considered either a full species, Larus thayeri (e.g. AOU 1998, Howell and Elliott 2001) or a dark-winged subspecies of Iceland Gull (e.g. Salomonsen 1951, Macpherson 1961, Godfrey 1986, Weir et al. 2000). In this paper we use Iceland Gull only for nominate glaucoides, and use Kumlien’s and Thayer’s for kumlieni and thayeri types, respectively.

Long ago, William Brewster (1883) described “an apparently new gull from eastern North America,” which he named Larus kumlieni - the “Lesser Glaucous-winged Gull." This taxon has since become known as Kumlien’s Gull and is usually treated as a subspecies of Iceland Gull (L. glaucoides), e.g. by Godfrey (1986) and AOU (1998). The relationship of Kumlien’s Gull and Iceland Gull to Thayer’s Gull, however, remains contentious, with the latter taxon considered either a full species, Larus thayeri (e.g. AOU 1998, Howell and Elliott 2001) or a dark-winged subspecies of Iceland Gull (e.g. Salomonsen 1951, Macpherson 1961, Godfrey 1986, Weir et al. 2000). In this paper we use Iceland Gull only for nominate glaucoides, and use Kumlien’s and Thayer’s for kumlieni and thayeri types, respectively.

Zimmer (1991) provided a useful review of plumage variation in Kumlien’s Gull, while more recently Garner and Mactavish (2001) discussed the identification of Kumlien’s Gull and Thayer’s Gull. These and other authors have commented on the highly variable appearance of Kumlien’s Gull, which apparently spans the spectrum from white-winged birds (like Iceland Gulls) to dark-winged birds (like Thayer’s Gulls). But just how variable are Kumlien’s Gulls? And are there patterns to their variation? Howell and Elliott (2001) noted that “Kumlien’s Gull cannot be defined satisfactorily until an attempt is made to define the characters of Thayer’s Gull (and Iceland Gull)”; as a starting point, they described variation in adult Thayer’s Gulls wintering in central California, USA. Here, we build upon that work by describing characters of, and quantifying variation in, adult Kumlien’s Gulls wintering on the Avalon Peninsula in eastern Newfoundland, Canada.

Although identifying gull taxa away from the breeding grounds carries inherent implications of uncertainty, in this case the wintering grounds may be at least as well defined as the breeding grounds. That is, on the breeding grounds it appears that "we can’t learn how much they [= Kumlien’s and Thayer’s] interbreed until we can distinguish them, but we can’t distinguish them because they appear to interbreed" (Howell 1998). And, as pointed out by

Garner and Mactavish (2001) and by Howell and Elliott (2001), researchers on the breeding grounds of these gulls have not critically defined the characters of what they called “Kumlien’s” and “Thayer’s.” (Links to Thayer's and presumed interbreeds: No 1, No 2.)

Although identifying gull taxa away from the breeding grounds carries inherent implications of uncertainty, in this case the wintering grounds may be at least as well defined as the breeding grounds. That is, on the breeding grounds it appears that "we can’t learn how much they [= Kumlien’s and Thayer’s] interbreed until we can distinguish them, but we can’t distinguish them because they appear to interbreed" (Howell 1998). And, as pointed out by

Garner and Mactavish (2001) and by Howell and Elliott (2001), researchers on the breeding grounds of these gulls have not critically defined the characters of what they called “Kumlien’s” and “Thayer’s.” (Links to Thayer's and presumed interbreeds: No 1, No 2.)

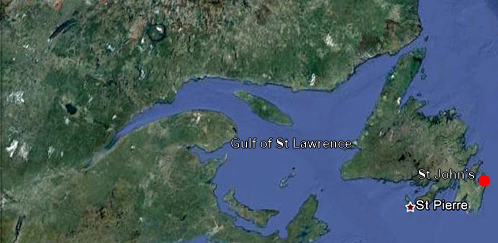

Methods

Kumlien’s Gulls winter mainly in the North Atlantic (AOU 1998), with large concentrations in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and around Newfoundland, in eastern Canada. We assumed that birds wintering in Newfoundland could be called Kumlien’s Gulls and quantified their variation before examining the data for patterns. Thayer’s Gulls winter primarily along the Pacific coast of North America from southern British Columbia to California. Mactavish has lived with thousands of wintering Kumlien’s Gulls for over 20 years. Howell has lived with hundreds of wintering Thayer’s Gulls for over 10 years and, in February 2002, visited Newfoundland to study Kumlien’s Gull. For this paper we quantified the plumage of over 400 adult Kumlien’s Gulls studied at close range from early February to early March 2002; our sample was unbiased, that is, we did not select for dark-winged or white-winged birds. We recorded data on the pattern and darkness of markings on primary 10 (P10, i.e. the outermost primary) inward through P5, and on eye colour, as well as noting general features of structure, bare-part colours, and overall tone of the upperparts relative to American Herring Gulls (L. argentatus smithsonianus) and “Canadian Glaucous Gulls” (L. hyperboreus leuceretes). We checked all birds for signs of immaturity (e.g. a brownish wash to the primary markings, relatively small white tips to P7-P9 and dark marks on the primary-coverts and tail) and restricted our wingtip analysis to 398 birds in at least their 4th winter (i.e. in 4th basic plumage and beyond). Under field conditions, such birds would be considered adults by most birders.

For wingtip pattern, the outer primaries were scored in terms of the extent of darker grey markings on the feathers (Plate 1). On some birds with a score of 1 the faint darker speckling was almost impossible to detect. Thus, some birds with a score of 0 may have had faintly darker areas that were overlooked; still, in terms of field identification these birds showed all-white wingtips. See e.g. this bird and this bird with limited pigmentation in the outer primaries. Because of the difficulty in viewing P5 (which, on resting birds, is usually covered by the tertials) and P10 (usually cloaked by P9) we were only able to obtain complete wingtip scores (P5 through P10) for 219 of 398 birds.

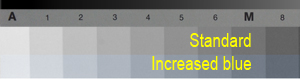

For the darkness of the grey pattern on the wingtip, we used six gradations from white to blackish grey, as follows:

For the darkness of the grey pattern on the wingtip, we used six gradations from white to blackish grey, as follows:

0 - white (Kodak 0);

1 - pale grey, similar in shade to upperparts and primary bases (Estimated Kodak 3-4);

1.5 - medium-pale grey (Estimated Kodak 5-6);

2 - medium grey (Estimated Kodak 7-10);

2.5 - medium-dark grey (Estimated Kodak 11-13);

3 - blackish grey (Estimated Kodak 14-17).

Values relative to the Kodak Grey Scale (catalogue number 152-7662; whereby 0 = white, 19 = black) were estimated by Howell, but should only be viewed as approximate, given the inherent difficulties related to ambient lighting, the angle at which the bird is standing, and observer perceptions under variable field conditions. For example, wingtips of score 2 can easily look darker (2.5 or even 3) in low light (such as late in the day) or with backlit reflection for birds standing on ice. Photos of birds against ice and snow often tend to be underexposed and, thus, misrepresent wingtip shades.

For the sake of consistency, we used the same scores for eye colour as those of Howell and Elliott (2001):

0 - iris uniformly dark brown;

0.5 - iris overall medium brown;

1 - iris overall pale brown or honey coloured;

1.5 - greenish or yellowish, extensively mottled brown;

2 - pale greenish or yellowish, moderately marked with brown;

2.5 - pale greenish or yellowish with little or no brown mottling visible;

3 - apparently unmarked pale yellow (like an adult Herring Gull but typically slightly darker yellow).

Results and Discussion

First we describe, quantify, and discuss variation in the wingtip pattern, dorsal colouration, and eye colour of winter adult Kumlien’s Gulls, and then discuss field identification of Kumlien’s relative to similar taxa. In light of comparable studies on the range of variation in other populations of Kumlien’s and Thayer’s Gulls, our comments about field identification may need to be refined, but we offer them here with a view to helping resolve an identification conundrum. We did not attempt to sex the birds in our sample, but we did not detect any appreciable differences in wing-pattern or eye colour among larger (presumed male) and smaller (presumed female) birds.

Wingtip Pattern and Dorsal Colouration

Wingtip pattern is often an important character in gull identification, and in this regard an appreciation of variation within each taxon is critical. The effect of age (including that of so-called “adult” birds) should also be considered, as discussed by Howell and Elliott (2001). For example, on British Herring Gulls and Lesser Black-backed Gulls of a known age, the wingtip pattern can continue to change up to age seven or older (M. T. Elliott, in prep.). In general, more white and less black develops on the wingtip with greater age. Clearly this has a potentially important bearing on the characterisation of "diagnostic" wingtip patterns for different taxa, but how variation in Kumlien’s Gull wingtip patterns could be age-related must await study of birds whose age is known.

The wingtips of perched adult Kumlien’s Gulls typically (77% of N = 185) appear “medium grey” (estimated Kodak 7-10; type specimen = Kodak 7-8; Table 1; Photos). Such markings are obviously darker than the upperparts, but clearly paler than the blackish grey (Kodak 14.5-17; score = 3) typical of Thayer’s Gull (Howell and Elliott 2001). A further 9% of birds had medium-pale (estimated Kodak 5-6) to medium-dark (estimated Kodak 11-13) wingtips, while 6% appeared all white (Kodak 0) and only 5% blackish grey (estimated Kodak 14-17).

In a sample of 190 birds, the inner web and outer web portions of the subterminal bands were not appreciably different in shade on 184 birds (97%), while on six (3%) the outer web appeared darker than the inner web by one category (cf. wingtip scores). Grey markings on the outer four to five primaries were overall similar in tone (see here), perhaps with a tendency for markings on P7-P8 to average darker or at least more "solid", than those on P6 and P9.

|

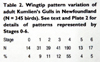

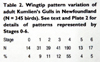

Primary pattern variation can be envisioned by starting with an unmarked wingtip (Stage 0; Plate 2, a) and building upon this (Table 2, Plate 2).

Stage 1 (9% of N = 345 birds; bird A, bird B) is darker grey stripes on the basal to medial portions of the outer webs of one to four of P7-P10, but with no trace of dark subterminal bands (Plate 2, b-e); note the darker stripes can be difficult to see in the field.

Stage 2 (11%) is darker grey stripes on the outer webs of three to four of the outermost four primaries (i.e. P8-P10 or P7-P10) with partial to incomplete subterminal bands on one to three primaries among P7-P9 (Plate 2, d-f; bird C, bird D).

Stage 3 (12%) is darker grey or more extensive grey on the outer webs of the outermost four primaries plus complete (mostly narrow) subterminal bands on one to three primaries among P7-P9 (Plate 2, g-i; bird E, bird F); only 12% of Stage 3 birds had complete subterminal bands on all three primaries, and the subterminal band was narrow on all 44% of Stage 3 birds with a complete band on only one primary.

The commonest pattern (and that of the type specimen of Kumlien’s Gull) was Stage 4 (55%): darker grey or more extensive grey markings on the outer five primaries (P6-P10) with complete subterminal bands on zero to three feathers among P6-P9 (most commonly on two to three primaries; Plate 2, j-m). This was also the pattern considered typical of Kumlien’s Gull by Grant (1986). Only 4% of Stage 4 birds had no complete subterminal bands, 12% had complete subterminal bands on only one primary (95% on P8; Photo 15), 44% (and the type specimen) had complete subterminal bands on two feathers (88% on P7-P8) and 39% had complete subterminal bands on three feathers (97% on P7-P9).

More extensively patterned wingtips were uncommon.

Stage 5 (4%) is darker grey or more extensive grey markings on the outermost five primaries (P6-P10) with complete subterminal bands on P6-P9 (three to four primaries with wide bands; Plate 2, n, p).

Stage 6 (5%) is darker grey or more extensive grey markings on the outer six primaries, with complete subterminal bands on three to four feathers among P6-P9 (two to four primaries with wide bands; Plate 2, o, q; Bird G).

Of 345 birds, only 14 (4%) had no visible darkening on the outer webs of the outer primaries (Stage 0 = "white-winged"), although seeing darker markings in the field can be virtually impossible (see Bird H, Bird I, Bird J, Bird K, Bird L). The overall appearance (structure, dorsal tone, etc.) of such birds may be typical of other Kumlien’s Gulls, as in this Newfoundland research. Six of these 14 had unmarked pale eyes like Iceland Gull (score of 3); one had an eye score of 1.5 and seven had an eye score of 2.5. If the pale-eyed and white-winged birds were Iceland Gulls they made up only 1-2% of the Newfoundland wintering population.

We saw only one bird with a complete grey subterminal band on P10, and only one other bird had a P10 score of 3. Seventeen of 345 birds (5%) showed dark subterminal markings on P5 but never a complete subterminal band, although this does occur on Kumlien’s Gull, albeit rarely. Of these 17 birds, two showed characters of fourth-years; on at least six others (apparently adults) the P5 markings were paler than those on P6-P9 and the birds overall looked typical on Kumlien’s Gull. Thus, Kumlien’s Gull can show dusky subterminal markings on P5 (contra Zimmer 1991). (inconspicuous on this example bird).

The identity of birds with the darker and most extensively marked wingtips is problematic. They were certainly atypical of Kumlien’s Gull, as defined by our study. Are these simply dark-winged Kumlien’s Gulls or could they be hybrids with Thayer’s Gull? We are unable to answer this question satisfactorily, but the presence of hybrid Kumlien’s x Thayer’s gulls in Newfoundland would not be surprising because: a) they are gulls, in which hybridisation is quite frequent; and b) these taxa are reported to interbreed (e.g. Snell 1989).

Additional characters noted on a few of these dark-winged birds suggest that at least some were hybrids (including back-crosses) with Thayer’s Gull. Two birds with a P5 pattern score of 2 had overall dark primary markings (score = 3; Plate 2, p) and eye scores of 2-2.5. One of these birds (eye = 2.5) had a relatively long bill and its upperparts were slightly darker than the surrounding Kumlien’s Gulls. This bird could be claimed as a Thayer’s Gull, but to Howell it did not look quite as big billed and long winged as Thayer’s Gulls in California. We could not determine the pattern on P9 (cf. Howell and Elliott 2001). Of the 13 Stage 5 birds, one had slightly darker upperparts than surrounding Kumlien’s Gulls, a relatively sloping forehead and squared nape, a wingtip darkness score of 3 (Plate 2, q) and an eye score of 1.5; we could not see the P9 pattern. Its short bill was typical of Kumlien’s Gull. Another bird seen in February 2002 (but not part of the unbiased sample) had a relatively long bill, dark upperparts and extensively blackish wingtips (with a complete dark charcoal band on P5), and was possibly another hybrid. Small numbers of dark-winged birds seen in other years by Mactavish may also be hybrid / back-cross Thayer’s x Kumlien’s gulls.

Six other birds (all Stage 4) in our sample also had a wingtip darkness score of 3, but in other respects were not noticeably different from surrounding Kumlien’s Gulls. However, in the well-studied Western Gull (L. occidentalis) x Glaucous-winged Gull (L. glaucescens) hybrid zone in western North America, mantle and wingtip darkness are “among the best discriminators of hybrids” (Bell 1996). Thus, it could be that all the birds in our sample with a wingtip darkness score of 3 (and perhaps some with a score of 2.5) represented introgression with Thayer’s Gull. Such birds amounted to about 10% of the Newfoundland wintering population, but, as well as including some possible extreme Kumlien’s Gulls, this total could involve an unknown number of back-crosses. Birds showing two or more character traits suggestive of Thayer’s Gull (large bill, head shape, long wings, darker upperparts, darker wingtips) comprised only 1-2% of our sample. In California, Howell and Elliott (2001) noted about 2% of birds with possible Thayer’s x Iceland or Thayer’s x Kumlien’s characters. This all suggests that modern-day interbreeding between Thayer’s and other taxa is limited - or that the hybrids winter elsewhere.

The upperparts of Kumlien’s Gull are pale blue-grey, closer in tone to an American Herring Gull (which is slightly darker than Kumlien’s) than to a Canadian Glaucous Gull (which is paler). Kumlien’s upperparts appeared fairly consistent in tone among large numbers of adults. In one flock of 400 adult Kumlien’s, we noted two white-winged birds with noticeably (albeit slightly) paler and greyer (less bluish) upperparts. In structure these birds were typical of other Kumlien’s Gulls. They could have been Iceland Gulls, intergrade Kumlien’s x Iceland, or perhaps simply the pale extreme of Kumlien’s. In a sample of 345 adults for which we recorded wingtip data, only two birds had slightly but distinctly darker grey upperparts than the surrounding Kumlien’s Gulls. Both of these birds showed other characters (larger bill, dark wingtip markings etc.) that suggest interbreeding with Thayer’s Gull (see above). Still, it appears that most Kumlien’s Gulls do not vary much in the tone of their upperparts (which is Kodak 3.5-4.5; type specimen = Kodak 4).

The upperparts of Kumlien’s Gull are pale blue-grey, closer in tone to an American Herring Gull (which is slightly darker than Kumlien’s) than to a Canadian Glaucous Gull (which is paler). Kumlien’s upperparts appeared fairly consistent in tone among large numbers of adults. In one flock of 400 adult Kumlien’s, we noted two white-winged birds with noticeably (albeit slightly) paler and greyer (less bluish) upperparts. In structure these birds were typical of other Kumlien’s Gulls. They could have been Iceland Gulls, intergrade Kumlien’s x Iceland, or perhaps simply the pale extreme of Kumlien’s. In a sample of 345 adults for which we recorded wingtip data, only two birds had slightly but distinctly darker grey upperparts than the surrounding Kumlien’s Gulls. Both of these birds showed other characters (larger bill, dark wingtip markings etc.) that suggest interbreeding with Thayer’s Gull (see above). Still, it appears that most Kumlien’s Gulls do not vary much in the tone of their upperparts (which is Kodak 3.5-4.5; type specimen = Kodak 4).

To summarise, the wingtip pattern of adult Kumlien’s Gulls wintering in Newfoundland was variable, but 78% of birds (N = 345) had Stage 2 to Stage 4 wingtip patterns (Table 2, Plate 2) and 85% (N = 185) had medium-pale to medium-dark wingtip markings (Table 1). These can be viewed as typical Kumlien’s Gulls. At most only about 1-2% of the Newfoundland wintering birds show the characters of Iceland Gull, while another 1-2% or more could be hybrids (including back-crosses) with Thayer’s Gull.

Eye Colour

10.jpg) We recorded eye colour on 393 adult Kumlien’s Gulls (Table 3) and compared the percentages of each score with a sample of 283 adult Thayer’s Gulls (Howell and Elliott 2001). The modal eye score for Kumlien’s Gull was 2.5 (mean 2.44) and for Thayer’s Gull 1.5 (mean 1.47), agreeing with the general wisdom that Kumlien’s is relatively "pale eyed and Thayer’s “dark-eyed.” However, darker-eyed Kumlien’s Gulls than those in our sample do occur (pers. obs.), and pale-eyed Thayer’s are not rare (this page). Hence, eye colour is unreliable for identifying an individual bird.

We recorded eye colour on 393 adult Kumlien’s Gulls (Table 3) and compared the percentages of each score with a sample of 283 adult Thayer’s Gulls (Howell and Elliott 2001). The modal eye score for Kumlien’s Gull was 2.5 (mean 2.44) and for Thayer’s Gull 1.5 (mean 1.47), agreeing with the general wisdom that Kumlien’s is relatively "pale eyed and Thayer’s “dark-eyed.” However, darker-eyed Kumlien’s Gulls than those in our sample do occur (pers. obs.), and pale-eyed Thayer’s are not rare (this page). Hence, eye colour is unreliable for identifying an individual bird.

CONTINUE TO PARAGRAPH: Separation from Similar Species and Hybrids

Iceland Gull (kumlieni) H8 1st-2nd-3rd-4th cycle (2CY-5CY), 2013-2016, Quidi Vidi Lake, St. John's, Newfoundland. Picture: Peter Adriaens, Lancy Cheng & Alvan Buckley.

Iceland Gull (kumlieni) H8 1st-2nd-3rd-4th cycle (2CY-5CY), 2013-2016, Quidi Vidi Lake, St. John's, Newfoundland. Picture: Peter Adriaens, Lancy Cheng & Alvan Buckley. Iceland Gull (kumlieni) L9 4th cycle (5CY), January 27 2017, Quidi Vidi Lake, St. John's, Newfoundland. Picture: Lancy Cheng.

Iceland Gull (kumlieni) L9 4th cycle (5CY), January 27 2017, Quidi Vidi Lake, St. John's, Newfoundland. Picture: Lancy Cheng.Illustrations from "Identification and Variation of Winter Adult Kumlien’s Gulls"

Plate 2: “Adult” primary patterns of presumed Kumlien’s Gulls Larus [glaucoides] kumlieni (a-o), possible hybrid Kumlien’s x Thayer’s gulls (p-q) and an “average” Thayer’s Gull for comparison (r). All wingtips taken from birds seen in Newfoundland, Canada, during February 2002, except for Thayer’s Gull (from California, December 1999). Figures are arranged to show progressive development of wingtip patterns from all white to most extensively and darkly marked. Percentages in parentheses are relative frequency of Stages 0-6 in a sample of N = 345 birds.

Plate 2: “Adult” primary patterns of presumed Kumlien’s Gulls Larus [glaucoides] kumlieni (a-o), possible hybrid Kumlien’s x Thayer’s gulls (p-q) and an “average” Thayer’s Gull for comparison (r). All wingtips taken from birds seen in Newfoundland, Canada, during February 2002, except for Thayer’s Gull (from California, December 1999). Figures are arranged to show progressive development of wingtip patterns from all white to most extensively and darkly marked. Percentages in parentheses are relative frequency of Stages 0-6 in a sample of N = 345 birds. Table 1: Wingtip darkness scores for 185 adult Kumlien's Gulls in Newfoundland.

Table 1: Wingtip darkness scores for 185 adult Kumlien's Gulls in Newfoundland. Table 2: Wingtip pattern variation of

adult Kumlien’s Gulls in Newfoundland

(N = 345 birds).

Table 2: Wingtip pattern variation of

adult Kumlien’s Gulls in Newfoundland

(N = 345 birds).13.jpg) Table 3 & 4: Iris colour variation in 393 adult Kumlien’s Gull from Newfoundland and in 283 adult Thayer’s Gulls from California.

Table 3 & 4: Iris colour variation in 393 adult Kumlien’s Gull from Newfoundland and in 283 adult Thayer’s Gulls from California.FEBRUARY ADULT IMAGES BELOW:

Example adults for the months January-February. Birds are categorized by wing-tip melanism, according to this classification. You can download the scoring sheet HERE (4,79 MB, to print), to do your own field research on flocks of adult birds.

Stage 0, unmarked white wingtip.

Stage 0, unmarked white wingtip. Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05-12 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 2 (1%>5% speckling).

Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05-12 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 2 (1%>5% speckling). Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling).

Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling). Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling).

Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 05 2012, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling). Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 06 2008, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling).

Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 06 2008, Peterhead, Scotland. Pictures: Chris Gibbins. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 (0%>1% speckling).Feb01.jpg) Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 07 2011, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 - (0%>1% speckling). Note pale grey upperparts.

Iceland Gull (glaucoides) adult, February 07 2011, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 1 - (0%>1% speckling). Note pale grey upperparts..jpg) Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2012, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 5 (>50% speckling). Note darker grey upperparts than in glaucoides.

Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2012, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 5 (>50% speckling). Note darker grey upperparts than in glaucoides. Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2012, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 5 (>50% speckling). Note darker grey upperparts than in glaucoides.

Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2012, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Dave Brown. Primary: Stage 0. Iris: class 5 (>50% speckling). Note darker grey upperparts than in glaucoides. Stage 1, darker grey marks on the outer one to four primaries but no subterminal marks.

Stage 1, darker grey marks on the outer one to four primaries but no subterminal marks. Stage 2, darker grey marks on the outer three to four primaries with subterminal marks on one to three primaries.

Stage 2, darker grey marks on the outer three to four primaries with subterminal marks on one to three primaries. Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 10 2012, near Reykjavik - SW Iceland. Picture: Ómar Runólfsson. Primary: Stage 2. Iris: honey.

Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 10 2012, near Reykjavik - SW Iceland. Picture: Ómar Runólfsson. Primary: Stage 2. Iris: honey. Stage 3, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer four primaries with complete subterminal bands on one to three primaries.

Stage 3, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer four primaries with complete subterminal bands on one to three primaries. Stage 4, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer five primaries with complete subterminal bands on zero to three primaries.

Stage 4, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer five primaries with complete subterminal bands on zero to three primaries. Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2005, Nuuk, Greenland. Picture: Carsten Egevang. Primary: Stage 4. Iris: -

Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) adult, February 07 2005, Nuuk, Greenland. Picture: Carsten Egevang. Primary: Stage 4. Iris: - Stage 6, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer six primaries with complete subterminal bands on three to four primaries among P6-P9.

Stage 6, darker grey or more extensive grey marks on the outer six primaries with complete subterminal bands on three to four primaries among P6-P9.  possible Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) x Thayer's Gull (thayeri) adult, February 12 2007, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Primary: beyond Stage 6. Iris: class 3 (5%>25% speckling).

possible Kumlien's Gull (kumlieni) x Thayer's Gull (thayeri) adult, February 12 2007, St John's - Newfoundland, Canada. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Primary: beyond Stage 6. Iris: class 3 (5%>25% speckling).