Larus cachinnans

Larus cachinnans

(last update:

Greg Neubauer

Marcin Przymencki

Albert de Jong

Mars Muusse

In 2010, Chris Gibbins, Brian J. Small and John Sweeney published two extensive papers in Britsih Birds, dealing with Caspian Gull. Below, you will find the content of the first paper "Part 1: typical birds".

Part 1: INTRODUCTION & IDENTIFICATION

Part 2: JUVENILES (1CY birds in July–September)

Part 3: BIRDS IN THEIR FIRST WINTER (1CY/2CY birds in October–April)

Part 4: BIRDS IN THEIR FIRST SUMMER (2CY birds in May-September)

Part 5: BIRDS IN THEIR SECOND WINTER (2CY/3CY birds during October-April)

Part 6: OLDER IMMATURE PLUMAGES (3CY–5CY birds)

Below, we continue with PART 7: ADULTS. "we" in the text below refers to the original authors. If any errors occur in this text, please let me know and mail to marsmuusseatgmaildotcom.

Adults

Adult Caspian Gulls are best located in gull flocks by a combination of their peculiar jizz, and relatively dark, small-looking eyes that contrast with the white head (plate 86). Identification can then be confirmed by detailed study of bill proportions, primary pattern, bare-part colours and upperpart tone. The following sections deal with these features in turn; plates 87–96 show a selection of adult cachinnans, michahellis and Herring Gulls.

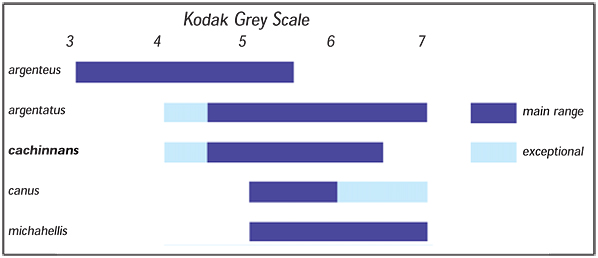

Fig. 2. Upperpart grey tones as represented on the Kodak Grey Scale for cachinnans and similar

taxa. Common Gull Larus canus is included as a good tonal match for cachinnans; values are for

nominate canus. The michahellis values exclude the Atlantic island populations (atlantis), which have

darker grey tones (from 7–7.5) than Iberian and Mediterranean birds. Values are based on Malling

Olsen & Larsson (2003) and Jonsson (1998).

Plumage

Fig. 2 shows the range of adult upperpart

tones for cachinnans and similar taxa, at least

in a British context. The figure uses the

Kodak Grey Scale, a scale that has numbered

increments from 0 (white) to 20 (black). The

scale itself is not reproduced here and most

gull-watchers will not go into the field armed

with a copy of it; fig. 2 simply compares the

upperpart tones among the various taxa and

shows the degree of overlap between them.

For grey-tone comparisons to be reliable,

other taxa should be directly alongside or

nearby. Observers also need to be aware of

the effects of light and viewing angle on the

perception of tone. Diffuse sunlight or overcast

conditions are best: strong direct sunlight

tends to bleach out subtle differences.

Another problem is that the grey tone may

appear to change on the same individual as it

faces in different directions relative to the

observer; upperparts tend to look darkest

when the bird is facing obliquely towards or

away from the observer. Thus, a slightly

darker-backed gull in a flock might just be

facing in a different direction from the

others. Any apparent difference should be

confirmed by seeing the bird in a variety of

positions.

The tone (darkness) of the pure grey upperpart feathers of adult and near-adult gulls is of quite limited value in cachinnans identification, because it overlaps extensively with that of other species. Nonetheless, it can be useful when looking for the species among paler-mantled argenteus in Britain (although most darker birds will turn out to be argentatus or michahellis, depending on location and season). To the practised eye, cachinnans can be located in flocks of michahellis by their subtly paler upperpart tone. Common Gull is usually a close match for cachinnans and, when alongside, can be used as a tonal marker.

Regardless of tone, there is a subtle difference in colour hue between the upperparts of cachinnans and Herring Gull, when seen in good light and in direct comparison. That of cachinnans is a more neutral, silky grey, with less of a bluish hue than either argentatus or argenteus. The upperparts of michahellis are more of a slate-grey. The human eye is a per perceptive tool and it is certainly possible to see the differences in colour hue between these species in direct comparison. However, because of differences between how observers perceive and describe colour, it is difficult to articulate the differences here, in words.

Wing-tip pattern

Adult cachinnans have a characteristic wingtip

pattern and, particularly when multiple

features in the wing-tip are used simultaneously,

this can be a good means of identification

(fig. 1 and plate 49). However, the

wing-tip pattern is not truly diagnostic,

because of a degree of overlap with argentatus Herring Gull.

The outermost primary (P10) of cachinnans is black, except for a long, pale 'tongue' on the inner web (grey on the upperside of the feather, white on the underside) and a long white tip. The black separating the tongue from the white tip is narrower than the length of white tip. This pattern is never seen in michahellis and is very rare in argenteus; however, it is common in argentatus. The details of the P10 pattern may be difficult to see well on flying birds (except, of course, in photographs) but can often be seen on a standing or swimming bird by viewing the underside of the folded wing. Occasional variations in the P10 pattern of cachinnans include cases where the pale tongue breaks through the black to merge with the white tip – a pattern typical of Thayer's Gull L. (glaucoides) thayeri.

An

example of this from Ukraine is shown by

Liebers & Dierschke (1997, plate 289), while

CG has seen such birds in Romania (Lake

Histria, September 2006). These locations

suggest that the 'thayeri pattern' occurs occasionally

in pure cachinnans, rather than being

indicative of introgression with Herring Gull.

Some birds show a small amount of black

within the long white tip of P10: of 31 adult

cachinnans examined in the hand by Liebers & Dierschke (1997), 11 showed a subterminal

black band (complete or incomplete) across

the tip of P10. There is also variation and

overlap among the taxa with respect to the

exact shape of the pale tongue, especially

between cachinnans and argentatus (Gibbins

2003). To reiterate, the P10 pattern is not

diagnostic.

Long, pale grey tongues are also present

on the inner webs of P7–P9 of cachinnans and, collectively, these give the impression of

pale wedges eating into an otherwise black

wing-tip. This pattern is very different from that of michahellis (which has a solid

black wing-tip) but is

seen on many argentatus.

Black extends

inward as far as P5 on

cachinnans and on

some (16%; Jonsson

1998) also to P4.

Ideally, a candidate cachinnans should have

a black band extending

unbroken across both

webs of P5, typically

slightly less deep than

that of michahellis.

However, there is considerable

variation in

the pattern of black on

P5 of all the taxa.

Around 10% of cachinnans lack a complete

black band on P5

(Jonsson 1998): such

birds may have isolated

marks on both the

inner and outer webs

of the feather (plate

49) or have black

restricted to the outer web. Herring Gulls

may lack black on P5 altogether (e.g. many

Norwegian argentatus), have black only on

the outer web (frequent in argenteus) or have

black on both webs. When black is present on

both webs of P5 in Herring Gull, it may be as

an isolated black spot on each (usually larger

on the outer web), or as a complete band

(plate 90). When present, the band is usually

much narrower than on michahellis, but it

matches many cachinnans. Black on both

webs of P5 is a surprisingly common feature

in eastern Baltic populations of Herring Gull

(Malling Olsen & Larsson give a value of

30%), so these birds are a real cause of confusion.

Overall, the variability in P5 pattern

means that it is difficult to give definitive criteria

regarding its value in identification. Like

cachinnans, Herring Gulls can have black

extending inwards as far as P4, though this is

rare.

Some have argued that eastern and western populations of cachinnans differ with respect to primary pattern (e.g. Stegmann 1934). Adults from eastern populations normally have a less extreme wing-tip pattern, where the long white tip of P10 is regularly interrupted by small black spots on each web, sometimes merging to form a subterminal band. A significant proportion show black on P4 (50%; Jonsson 1998). Compared with western birds, eastern cachinnans may also show shorter pale tongues invading the black of the upperwing, but these still break up the black of the outer primaries in a way that michahellis never shows. More research is needed to determine whether eastern and western cachinnans deserve formal subspecies status.

Head pattern

The head of adult cachinnans normally

appears unmarked (plate 87). Any streaks are

extremely fine, often confined to the lower

rear neck, and usually only apparent at close

range for a limited period in autumn (plate

88). In michahellis, streaking is also usually

apparent only in the autumn but is concentrated

around the face and ear-coverts. On

average, this streaking is clearer than shown

by cachinnans at this time. Streaking disappears

in late autumn, as feathers wear. From

early autumn to mid/late winter, the vast majority of Herring Gulls show a variable but

usually obvious degree of dusky streaking

and/or blotching on the head and neck (plate

90). There are exceptions and it is possible

(though uncommon) to find clean-headed

argenteus and argentatus before January, just

as it is possible to find the odd Black-headed

Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus with a full

hood in mid-winter.

Bare parts

Outside the breeding season, the bill of

cachinnans is normally a rather weak,

greenish-yellow, fading to grey-green basally.

There are frequently some dark marks (small

spots or crescents) in the gonys, while the red

is usually less bright than for either michahellis or Herring Gull. Thus, in general, the

bill of cachinnans in winter stands out as

being duller than that of the other species.

However, as many argentatus have washed-out,

greeny-yellow bills in winter, bill colour

and pattern is merely a supportive feature.

The bill becomes a richer yellow in late spring and, during the breeding season the bill coloration of cachinnans overlaps with that of Herring Gull. Neubauer et al. (2009) argued that, unlike the orbital ring (see below), bill tones do not differ consistently between cachinnans and Herring Gull in breeding plumage. The bill of cachinnans is distinctly duller than the bright, orange-toned bill of michahellis; moreover, the red gonys spot of michahellis is extremely bright and regularly spreads extensively onto the upper mandible.

In the field, most adult cachinnans appear

dark-eyed; in fact, the iris is not wholly dark,

but peppered by dark brown spots.

Depending on the density of these spots, the

iris may appear dirty amber-yellow or uniformly

dark brown, but never completely

black. Eye colour varies enormously in

cachinnans: Jonsson (1998) suggested that c.

75% of adult cachinnans appear 'medium- to

dark-eyed' in the field, whereas Liebers& Dierschke (1997) found that 48% of birds in

one Ukrainian colony and 62% in another

were 'pale-eyed'. Much depends on how 'dark'

is defined. Most birds do look darker-eyed in

the field than typical Herring Gulls or michahellis and truly pale (clean yellow) eyes are

rare in cachinnans (<10% Jonsson 1998;

2–5% Hannu Koskinen pers. comm.). Note

also that some apparently adult Herring

Gulls have dark peppering in the iris and

some look genuinely dark-eyed in the field

(plate 96); anyone checking large numbers of

Herring Gulls should expect to find darkeyed

birds with moderate regularity.

The orbital ring of cachinnans varies from

pale orange to red (Liebers & Dierschke 1997;

Neubauer et al. 2009). That of Herring Gull

varies from yellow (typical argenteus),

through pure orange to orangey red; that of

some Baltic argentatus looks deep red and

thus approaches michahellis. Orbital ring

colour in Herring Gulls has been shown to

differ among birds breeding in the same

colony (Muusse et al. unpubl.). Thus, while

orbital-ring colour is a useful feature for

cachinnans (orange to red is acceptable,

yellow is a problem), it is merely one of a

number of features that combine to make the

species distinctive but which are not individually

diagnostic. Liebers & Dierschke (1997)

reported a correlation between iris and orbital ring colour – pale-eyed cachinnans having pale orange orbital rings and dark-eyed

birds having redder orbitals – and this

relationship is clearly worth further study.

The leg colour of adult cachinnans varies seasonally and individually. In winter, the legs are typically pale, greyish-flesh; some have a weak, greenish-yellow tint. In spring and early summer, the legs of many adults become distinctly brighter and yellowish. The proportion showing truly yellow legs during the breeding season is uncertain and may vary among populations and even from year to year (perhaps linked to diet). The leg colour of an individual bird can vary during the course of the breeding season, probably as a function of physiological condition (Neubauer et al. 2009). There is complete overlap in leg colour between cachinnans and the Herring Gulls of the eastern Baltic (from pure pink to lemon yellow) so this feature is of limited value. However, cachinnans rarely matches the rich yellow of the legs of michahellis.

Pitfalls

The most likely problem is confusion with a

Herring Gull from the eastern Baltic. These

are quite unlike the Norwegian argentatus that we are familiar with in the UK and can

have upperpart tones, bare-part colours and

wing-tip patterns that are virtually identical

to those of cachinnans. The potential for confusion

is increased by the fact that these

argentatus may look slightly longer-winged,

longer-legged and longer-billed than argenteus (although less obviously so than cachinnans).

The occasional dark-eyed bird can

create real problems.

Concluding remarks

The aim of part 1 of this paper has been to

describe the appearance of typical Caspian

Gulls. The birds featured in the plates are all

rather typical and should not pose any identification

problems. Variability is a feature of

large gulls, however, and observers should

not expect all cachinnans to look identical.

Nonetheless, there is what might be regarded

as normal or typical variation (that outlined

above) and that which is extreme or atypical.

In part 2 we shall deal with the extremes and

discuss birds that sit in the overlap zones

between the species. We shall also consider hybrids; this is a very real problem given that hybridisation is occurring in Poland, for

example, and that hybrids originating there

have been recorded in Britain. Before

becoming embroiled in debates about the

more difficult individuals, it is important

that birders are familiar with the identification

of typical birds. We hope that part 1 has

provided this familiarisation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nic Hallam, Hannu

Koskinen, Ian Lewington and four anonymous

reviewers, whose insightful comments greatly

improved this manuscript. We are also grateful to Ruud

Altenburg, Steve Arlow, Hannu Koskinen, Mike

Langman and Pim Wolf for sharing and allowing us to

use their photographs. A number of birders shared

their knowledge and experience of cachinnans during

the preparation of this paper; we especially thank

Ruud Altenburg, Hannu Koskinen, Mars and Theo

Muusse and Visa Rauste in this regard. Dmitri Mauquoy

kindly produced fig. 1.

References

Bakker, T., Offereins, R., & Winter, R. 2000. Caspian Gull

identification gallery. Birding World 13: 60–74.

Collinson, J. M., Parkin, D.T., Knox, A. G., Sangster, G., & Svensson, L. 2008. Species boundaries in the Herring

and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex. Brit. Birds 101: 340–363.

Garner, M. 1997. Large white-headed gulls in the

United Arab Emirates: a contribution to their field identification. Emirates Bird Report 19: 94–103.

— & Quinn, D. 1997. Identification of Yellow-legged

Gulls in Britain. Brit. Birds 90: 25–62.

Gibbins, C. N. 2003. Phenotypic variability of Caspian

Gull. Birding Scotland 6: 59–72.

Grant, P. J. 1986. Gulls: a guide to identification. 2nd edn.

Poyser, London.

Gruber, D. 1995. Die Kennzeichen und das Vorkommen

de Weißkopfmöwen Larus cachinnans in Europe.

Limicola 19: 121–127.

Howell, S. 2001. A new look at moult in gulls. Alula 7:

2–11.

Jonsson, L. 1998.Yellow-legged Gulls and yellow-legged

Herring Gulls in the Baltic. Alula 4: 74–100.

Klein, R. 1994. Silbermöwen Larus argentatus und

Wei‚kopfmöwen Larus cachinnans auf Mülldeponien

in Mecklenburg – erste Ergebnisse einer

Ringfundanalyse. Vogelwelt 115: 267–285.

Leibers, D., & Dierschke,V. 1997.Variability of field

characters in adult Pontic Yellow-legged Gulls. Dutch

Birding 19: 277–280.

—, Helbig, A. J., & de Knifff, P. 2001. Genetic

differentiation and phylogeography of gulls in the Larus cachinnans-fuscus group (Aves:

Charadriiformes). Molecular Ecology 10: 477–2462.

Malling Olsen, K., & Larsson, H. 2003. Gulls of Europe,

Asia and North America. Helm, London.

Neubauer, G., Zagalska-Neubauer, M. M., Pons, J-M.,

Crochet, P-A., Chylarecki, P., Przystalski, A., & Gay, L. 2009. Assortative mating without complete

reproductive isolation in a zone of recent secondary contact between Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus)

and Caspian Gulls (L. cachinnans). The Auk 126:

409–419.

Small, B. 2000. Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans in Suffolk – identification and status. Suffolk Birds 49: 12–21.

Stegmann, B. K. 1934. Ueber die Formen der Großen

Möwen ('subgenus Larus') und ihre gegenseitigen Beziehungen. J. Orn. 82: 340–380.

Larus cachinnans 7CY UAK T-001380 September 23 & October 14-27 2010, Westkapelle, the Netherlands. Pictures: Theo Muusse & Ies Meulmeester.

Larus cachinnans 7CY UAK T-001380 September 23 & October 14-27 2010, Westkapelle, the Netherlands. Pictures: Theo Muusse & Ies Meulmeester.  Larus cachinnans adult UKK ? September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult UKK ? September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.  Larus cachinnans adult PUHU September 17 2011, Wistula River in Mazowieckie, Poland. Picture Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans adult PUHU September 17 2011, Wistula River in Mazowieckie, Poland. Picture Michal Rycak. Larus cachinnans 6CY-8CY 671P October 2008, September & November 2010, Boulogne-sur-Mer, NW France, Picture: Jean-Michel Sauvage.

Larus cachinnans 6CY-8CY 671P October 2008, September & November 2010, Boulogne-sur-Mer, NW France, Picture: Jean-Michel Sauvage. Larus cachinnans adult 47P3 April 30 2008, Włocławek Reservoir, central Poland. Picture: Magdalena Zagalska-Neubauer & September 17 2008, Boulogne-sur-Mer, NW France, Picture: Jean-Michel Sauvage.

Larus cachinnans adult 47P3 April 30 2008, Włocławek Reservoir, central Poland. Picture: Magdalena Zagalska-Neubauer & September 17 2008, Boulogne-sur-Mer, NW France, Picture: Jean-Michel Sauvage. Larus cachinnans hybrid 2CY, 5CY & 7CY 4P60 June 2005 UK, September 2008 Lithuania, January 2010 Austria.

Picture: Dick Newell, Hannu Koskinen & Wolfgang Schweighofer.

Larus cachinnans hybrid 2CY, 5CY & 7CY 4P60 June 2005 UK, September 2008 Lithuania, January 2010 Austria.

Picture: Dick Newell, Hannu Koskinen & Wolfgang Schweighofer. Larus cachinnans 5CY KN76 September 25 2010, Jastarnia, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak.

Larus cachinnans 5CY KN76 September 25 2010, Jastarnia, Poland. Picture: Michal Rycak. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.  Larus cachinnans adult, September 11 2011, Baku, Azerbaijan. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 11 2011, Baku, Azerbaijan. Picture: Chris Gibbins.  Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 10-20 2010, Preila Pier - Neringa Spit, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.  Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.  Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 2010, Dumpiai dump - Klaipeda, Lithuania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins.

Larus cachinnans adult, September 23 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Arrested moult in primaries?

Larus cachinnans adult, September 23 2011, Ashdod, Israel. Picture: Amir Ben Dov. Arrested moult in primaries?

Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Portret.

Larus cachinnans adult, 12-20 September 2008, Mamaia, north of Constanta on the Black Sea coast of Romania. Picture: Chris Gibbins. Portret.